Police secrecy on Stingray cellphone surveillance device challenged

Stingray device allows law enforcement to secretly track cellphones

A police department's refusal to either confirm ordeny the use of a controversial and indiscriminate mass-surveillance

device means Canadians have no way of knowing if their personalcellphone data is safe from prying eyes, say civilrights groups.

Pivot Legal Society, a British Columbia-based legal-advocacy organization, filed an appeal with the province's privacy commissioner after Vancouver police refused to disclose documents related to whether they use an invasive technology known as Stingray.

"Citizens do not have an opportunity to be part of an engagementof how these devices are being used, how their data is being used," said Pivot spokesman Kevin Hollett.

"When police refuse to be transparent about their investigative techniques,this becomes incredibly problematic for the public."

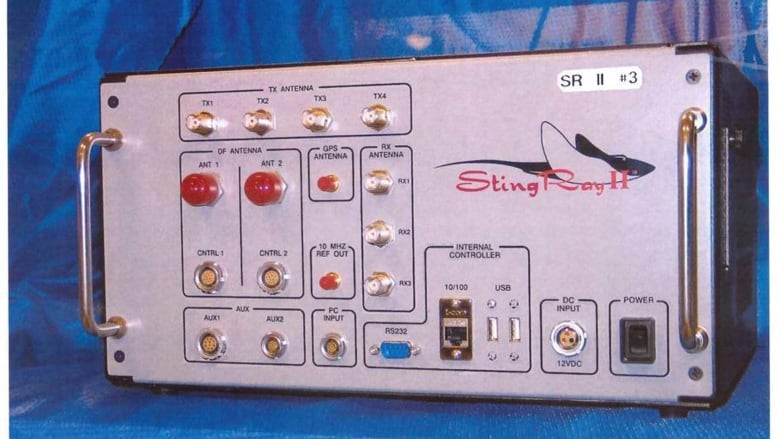

Stingray is a device that mimics a cellular communications towerto trick mobile devices within range to connect to it. This allowsthe cell-site simulator to intercept both text and audiocommunication, as well as to extract internal data and pinpoint adevice's location.

The device, which operates as a dragnet interceptor, has alsobeen referred to as a King Fisher, an IMSI catcher and a cell-sitesimulator.

Police accused of 'stonewalling'

Wednesday was the deadline for interveners to file submissions onPivot Legal's appeal.

Groups such as the B.C. Civil Liberties Association and OpenMediaargue that police are "stonewalling" attempts by the public toknow the extent of the device's use, which is putting Canadians'constitutional rights at risk and preventing law enforcement frombeing held accountable.

In its submission, filed on Wednesday, OpenMedia wrote thatconfirming Stingray use is a necessary precursor to theinformedpublic debate needed to develop appropriate policy and legalguidelines.

"(It) is therefore in the public interest for such disclosure tooccur."

The BCCLA's submission posited police accountability andregulatory oversight as the core issues.

"The simple fact that we cannot get police to even confirm nordeny whether they exist or whether they're planning to use themmeans that that critical piece of policy and legal work is preventedfrom happening," said spokeswomanMicheal Vonn.

"It really is the major roadblock to us shaping the rules forpolice use around these devices."

Compromised investigations

Vancouver police have argued that divulging documents on thetopic could compromise the effectiveness of their investigativetechniques.

"We take an individual's privacy very seriously and continue to follow strict legal requirements to obtain and utilize personal information," said Vancouver police Sgt. Randy Fincham.

But Chris Parsons, of the Munk School of Global Affairs' CitizenLab at the University of Toronto, dismissed that assertion, notingthat its use is widely acknowledged in the United States.

The American Civil Liberties Union has identified 61 agencies in23 states that own Stingray devices, though the group said thatnumber likely underrepresents the actual total given how manyagencies purchase the technology secretly.

Known groups include theFederal Bureau of Investigation, the National Security Agency andthe Internal Revenue Service.

"Let's face it, we've got TV shows where these things are comingup as plots devices," Parsons said.

"They're in the public domain.This isn't a top-secret device or something of that nature.Functionally, we understand how they operate, so asking anypolice service, 'Do you have these? And if so, can you providedocuments pertaining to them?' is a fairly trivial sort ofrequest."

Of more concern, he said, would be discovering that a policedepartment lacks policies or regulations around what to do withinformation collected from random citizens who are not underinvestigation.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)