'It's in their DNA': What makes people blow the whistle over their silent counterparts

'Whistleblowers ... [are] almost more heroic than somebody that's running into a burning building'

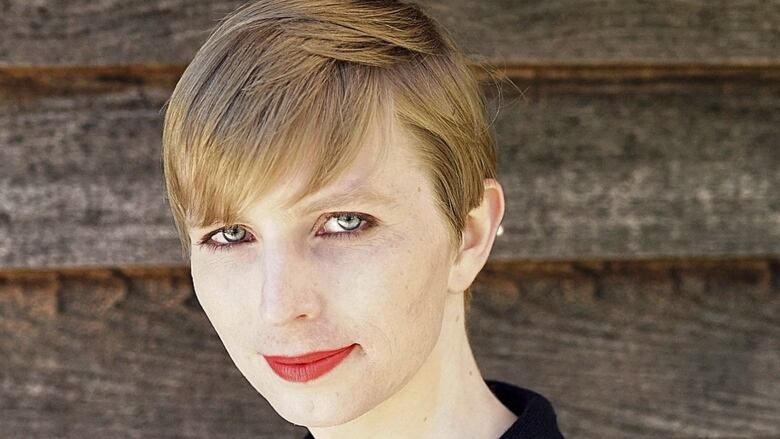

It's nice to believe that if we were in the position of Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning orAlyson Mosher and Kalen Christ we would have also blown the whistle.

But according to Zeno Franco, anassistantprofessor at the Medical College at Wisconsin, that's probably unlikely.

"What setswhistleblowersapart is they're able to continue to walk forward knowing that everyone's turning against them," he toldCBCGo Public's Erica Johnson.

"Stubbornessin that situation is actually a strength. It's in their DNA in that sense. They can't help but call us back to account."

Franco, who researches the social psychology of heroism, says the particular moral courage of whistleblowers has gone overlooked.

As part ofCBC Radio's Go Public specialWorkplace WhistleblowersJohnson spoke with Franco about what characteristics distinguish whistleblowers from the rest of us, and why he believes researchers have been afraid to study thesemodern-day mavericks.

So you study heroics, heroism and you say that whistleblowers fall under that category. How is that?

I think one of the definitions that we have of heroics is taking risky action either physically risky action or socially risky action in the service of a noble goalwithout the expectation of a personal reward. And whistleblowers do exactly that.

Usually they're facing some sort of social costsocial ostracism, being cast out of their workplace. And all of a sudden some issue comes up, and they say, "You know what? This is really not right and I'm going to break with the social group to say I don't agree with this." And that comes with a set of costs, real risks.

So why would someone do that? Break with the pack?

I think a lot of it has to do with valuing principle over social relationships.

Whistleblowers feel like, "This principle that I've believed in my whole life that's more important than keeping an even keel with my co-workers or with my friend." But that's a very scary position to be in. We are very social animals and we like to be in a group.

Whistleblowers... [are] almost more heroic than somebody that's running into a burning building. The process unfolds over time and thewhistleblowerhas multiple opportunities to withdraw.- Zeno Franco, assistant professor atMedical College at Wisconsin

What happens psychologically to someone once they start to blow the whistle?Often it's a long drawn-out process.

I think one of the forms of heroics that we've identified is this ability to keep at things and persist despite increasing costs. We often think of heroics as action, but there's also what I would describe as passive heroics, which is not complying when people are trying to make you do something that's wrong.

One of the things that happens is an element of self-doubt comes into play, creeps in, so you may really view the principle as incredibly important, but all of a sudden you've got five other co-workers saying you're doing wrong by breaking with what we're saying is the next set of action as a team what happens is people have self-doubt.

What sets whistleblowers apart is they're able to continue to walk forward knowing that everyone's turning against them. And they hold on to that ideal internally, even if they start to doubt themselves. Somehow they manage to hold on to that principle.

Often when we think of a hero, we think of someone dashing into a burning building to rescue a baby it's a split-second decision for that act of bravery. But when we come to whistleblowing, how often is that a split-second decision or have you found in your research these things simmer away until finally the whistleblower says, "This is it, I've got to speak out."

One of the arguments we've made is that actually whistleblowers and social heroes [are] almost more heroic than somebody that's running into a burning building. The process unfolds over time and the whistleblower has multiple opportunities to withdraw.

They come up to several different situations where they say, "This is crazy, this is too risky. I don't want to abandon my entire career over this one issue."Whistleblowers are often physically assaulted as well, but they keep going. And that's, I think, a form of heroics that we often don't think about.It's not just a single action. It's the individual encounters, multiple opportunities to exit and they continue to persist.

When we really studywhistleblowers... we are forced to be introspective and ask if ever I was put in that situation would I ever rise to that standard of behaviour? And frankly, most researchers are afraid of asking that question.- Zeno Franco, assistant professor atMedical College at Wisconsin

We have heard experts say it's part of their DNA that whistleblowers can't turn a blind eye when they see wrongdoing. What do you think?

I think it's a lot of things. I think it's nature and nurture, just like everything else. But I think that idea that it's so deeply ingrained in them, that "this principle is more important than what the social milieu is asking me to do" is something at their core. We often see stubbornness as a bad feature. Often times, we end up looking at people who are whistleblowers as an outsider in a workplace. But often times and this is what I think corporations need to understand, and teams in workplaces need to understand, too that stubborn personholds us as a group to account on the things that really matter.

Stubbornness in that situation is actually a strength. It's in their DNA in that sense. They can't help but call us back to account.

Whistleblowers haven't been explored very much in the past decade or so why is that?

I think when we really study whistleblowers and heroes we are forced to be introspective and ask if ever I was put in that situation, would I ever rise to that standard of behaviour? And frankly, most researchers are afraid of asking that question of themselves. It's a very challenging question. And so I think it's easy to shy away from this research because it's personally challenging. But we should. And I think we can't understand human behaviour fully until we understand human behaviour at its best.

Have you asked yourself that question?

Absolutely. Igive a couple of lectures on this and I share a point in my career where I failed to act heroically and that I regret. And I describe it openly to show people what it looks like and how you can learn from those mistakes. And hopefully, when you're encountering a similar situation in the workplace or on a sports team or whatever context that you know yourself well enough to be able to negotiate that situation and to stick with the things that you believe.

This segment was produced by EnzaUda, Jessica Linzey and Erica Williams.Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)