In 1939, Shakespeare pays a visit to a fictional residential school

'Were exploring what it is to do Shakespeare on this land say the playwrights

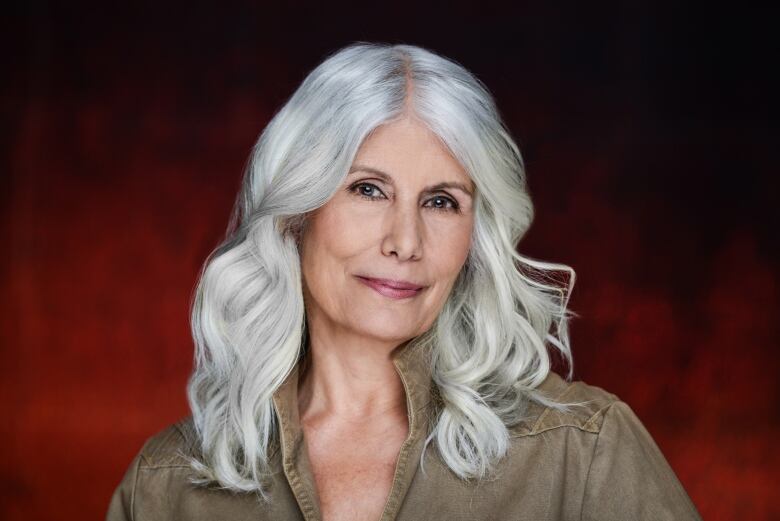

When playwrights Jani Lauzon and Kaitlyn Riordan began writing a play set in a residential school, they knew they'd start with Shakespeare.

"Kaitlyn and I just fell in," Lauzon tells CBC Arts. "We fell into a fantastic, deep, easy, immediate conversation about our love for Shakespeare. And I talked about my experience growing up, how my foster father was a lover of Shakespeare.

"But as an actor, when I got into that world, I realized that being who I was the colour of my skin didn't afford me the opportunities I expected," says the theatre artist, who's of Mtis, French and Finnish ancestry. "So I set out on a mission to find myself and my way of looking at the world within Shakespeare's text."

That's how 1939 was born. It's a coming-of-age tale that chronicles life in a fictional residential school as the students prepare a production of All's Well That Ends Well for a visit by King George VI. After premiering at the Stratford Festival in 2022, the play is being remounted this month at Canadian Stage in Toronto, and again at the Belfry Theatre in Vancouver in November. The story's as timely as ever, say Lauzon and Riordan, as Canadian theatre continues to interrogate its relationship with Shakespeare, and as Canada more broadly reconciles its history of abuse toward Indigenous peoples.

"We're really exploring what it is to do Shakespeare on this land," says Riordan, "and in a really deep way, we're looking at what it means to do Shakespeare as an Indigenous person. What is it to import culture?

"Shakespeare was used as a tool of colonization in many countries," she continues. "But Shakespeare cannot be defined by one single thread. The plays are too complex, too deep there's so much dichotomy and contradiction within Shakespeare."

Canada's artistic landscape has had a recent infatuation with All's Well That Ends Well. The Stratford Festival staged Shakespeare's so-called "problem play" in 2022, and novelist Mona Awad's All's Well centres a university production of the play in its witchy exploration of chronic pain.

For Lauzon and Riordan, All's Well That Ends Well was the perfect play-within-a-play for 1939, thanks to how it approaches themes of healing and medicine.

"In All's Well That Ends Well, Helena is the daughter of a medicine man," says Lauzon, who is also the play's director. "He's passed those gifts on to Helena, those recipes, which the colonial world doesn't believe in. We were also intrigued by the character of Bertram we looked at him through the lens of being a young Indigenous man who's been put into a situation where he's lost his sense of self.

"If we're looking at a young Indigenous man coming back to his community, what would it take to bring him back?," she muses. "We looked at [All's Well That End's Well]'s final scene as a reconciliation scene."

Lauzon and Riordan each brought decades of experience as writers, actors and directors to the development process. They say that background made for a particularly rich period of research and dramaturgy as they puzzled 1939 together.

"My acting really helps me inform my practice as a director," says Lauzon. "I'm able to put together the intentions, because I deeply understand the research And with having written the play, I have that deep, deep research inside me already. I'm really aware of the several worlds in which the play sits, and I'm able to bring in my experience as an actor to communicate those ideas to the cast in a supporting way."

Riordan agrees: Experience in multiple forms of theatre-making only enhanced the creative alchemy behind 1939.

"We were constantly reading scenes with each other while writing it. And that's so helpful, because we can ask, 'Is this line justified?' or 'Is the rhythm off?' And it was fun to then have to problem-solve the things we'd written the practices feed on themselves."

Finding humour in a fictional residential school

From early discussions, Lauzon and Riordan knew 1939 would have to include moments of levity and laughter.

"It's this idea of paradox in theatre, and the nuance and complexity that theatre allows us," says Riordan. "There are some amazing plays about residential schools, and they tell a certain aspect of the story, but people's experiences are as diverse as the human beings at these schools. If we were going to write this play and set it there, we wanted to make sure there was some humour in it, some lightness."

Riordan admits the first steps into the world of 1939 were "intimidating" as someone who hadn't worked intimately with residential schools or their troubled context.

"I was really beginning my journey of understanding this history," she says. "But it felt right in a deep way. And as we progressed, we recruited some amazing elders and survivors to help us guide this journey. The humour in 1939 was reinforced by them over and over again, and they were thankful for it, and asked for more of it." According to Riordan, some invited guests recognized the play's humour the fart jokes, and the boisterous pranks from their own experiences in residential schools. For them, says Riordan, humour was a means of survival, and a vehicle for love in an often dehumanizing environment.

"That's one of the biggest myths I want to bust," agrees Lauzon. "There's a myth that exists that the reason children were taken from their families was that Indigenous people did not have the capacity to love. The heart and love in the play is there to help bust that myth."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)