Chinese New Year celebrations create bridge between cultures

Historian Larry Wong says Year of the Horse festivities opportunity for inter-cultural understanding

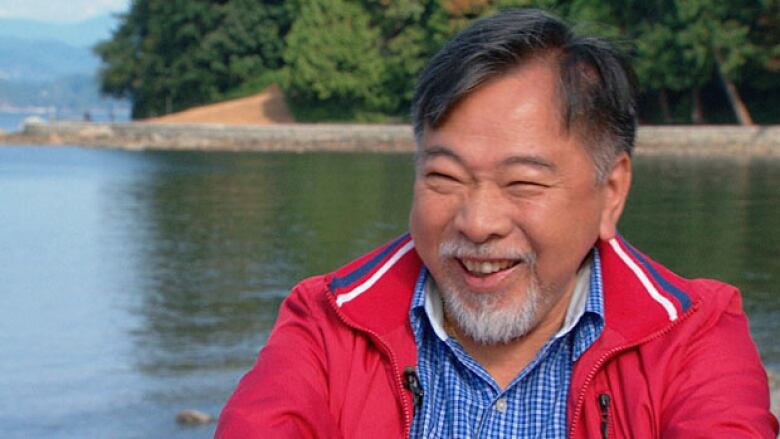

These days in Vancouver, Chinese New Year celebrations include people of all ethnicities. But according to historian Larry Wong, when he was growing up, non-Chinese residents didn't mix with the residents of Chinatown.

For Wong, who is now 75-years of age, Chinese New Year has always been a time to share food with family and friends.

The historian remembers big gatherings in the 1980s, when a family friend would scout out a restaurant outside of Vancouver's Chinatown. He says anything closer was simply too busy.

Wong's older brother, Wah, worked abroad for UNICEF and would only come home to Vancouver every two years.

"When he was on home leave on one of those celebrations, he had his two boys with him and his wife of course, and so we had a big celebration," he says.

Food was an important part of the festivities, and to this day, a whole fish, usually lingcod or rock cod, is Wong's favourite dish for the occasion.

"You have to cook or steam it just right, so it has a nice delicate flavour to it," he says. "You can tell when the fish is really fresh, because it has a bit of a sweet taste to it."

Beyond the flavour, the fish symbolises having plenty, and brings luck for the year to come.

Mysterious Chinatown opens up

Today, public Chinese New Year celebrations include people of all ethnicities, but according to Wong that wasn't always the case. The 75-year old says when he was young, non-Chinese residents didn't mix with the Chinese.

"Chinatown was considered as being very mysterious and closed off to society at large," says Wong. "Chinatown was always perceived as some place where people spoke a strange language and there was strange food."

As Wong sees it, New Year played an important role in changing that perception. He says it all began in the 1950s, with a man named Roy Mah. Mah published an English-language Chinese news magazine, the first of its kind in Canada. He wrote about Chinese New Year celebrations, and Wong says that prompted Business Associations in Chinatown to create public events, including a very popular beauty contest.

"You'd see candidates of young girls running for the crown of Miss Chinatown," says Wong.

"That brought a lot of publicity to Chinatown."

Restaurants joined in on the buzz, including the Marco Polo Supper Club, owned by brothers Victor, Harry and Alex Louie, who pioneered the all-you-can-eat Chinese buffet.

"[It] was enough to bring people coming over to find out what it was all about," says Wong.

"Of course having a choice of different foods, at a very low price, it was very very attractive."

While Wong grew up in Vancouver, he studies the history of the Chinese around the province.

Victoria has the oldest Chinatown in the country, and many immigrants would simply pass through Vancouver on their way to the interior. In the late 1800s and early 1900s mining brought immigrants from China to the interior.

"The town of Ashcroft had quite a bit of Chinese population after the gold mining and the railway building," says Wong.

"Some of them settled in Ashcroft as farmers. There's a story where they grew potatoes and their potatoes were such good quality that the Canadian Pacific Railway would buy them exclusively for their dining car."

It wasn't easy for those early Chinese immigrants.

Apology for historical wrongs

The B.C. government is currently consulting with Chinese communities, as it tries to apologize for a historical discrimination, including the head tax each Chinese immigrant was charged starting in the late 1800s.

"I think these things should be brought up, so we don't forget what happened in the past," says Wong.

"You let the history be written, or be shown, be displayed so that we do appreciate what we enjoy now."

Wong experienced the discrimination first hand. When he was born in Vancouver in 1938, he, and other Canadian-born Chinese weren't allowed to claim Canadian citizenship. That law didn't change until 1947.

In 1957, Wong applied for a job at a bank. He says he was turned down because he was Chinese.

"That was really shocking for me," he says.

"I couldn't believe my ears when the manager told me, 'I'm sorry, we don't like having Chinese being a bank teller and dealing with the public.'"

Three years later, the first Canadian Bill of Rights was introduced, making discrimination based on race illegal.

Wong says attitudes have changed as well, and points to Chinatown's annual New Year parade as an example.

"It's not just Chinatown celebrating New Year, really it becomes a multicultural affair," he says.

"The message is that Chinatown is willing to share its culture and celebration with other people. It's everyone's Chinese New Year."

How has Chinese culture shaped your community? Share your stories on B.C. Almanac onFriday, January 31st. Historian Larry Wong and Feng Shui Master Sherman Tai join host Mark Forsythe to ring in the Year of the Horse at the Aberdeen Centre in Richmond.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)