Privacy and public interest at odds in Surrey shooting investigation

Civil liberties advocates question RCMP decision to release photographs of unco-operative victims

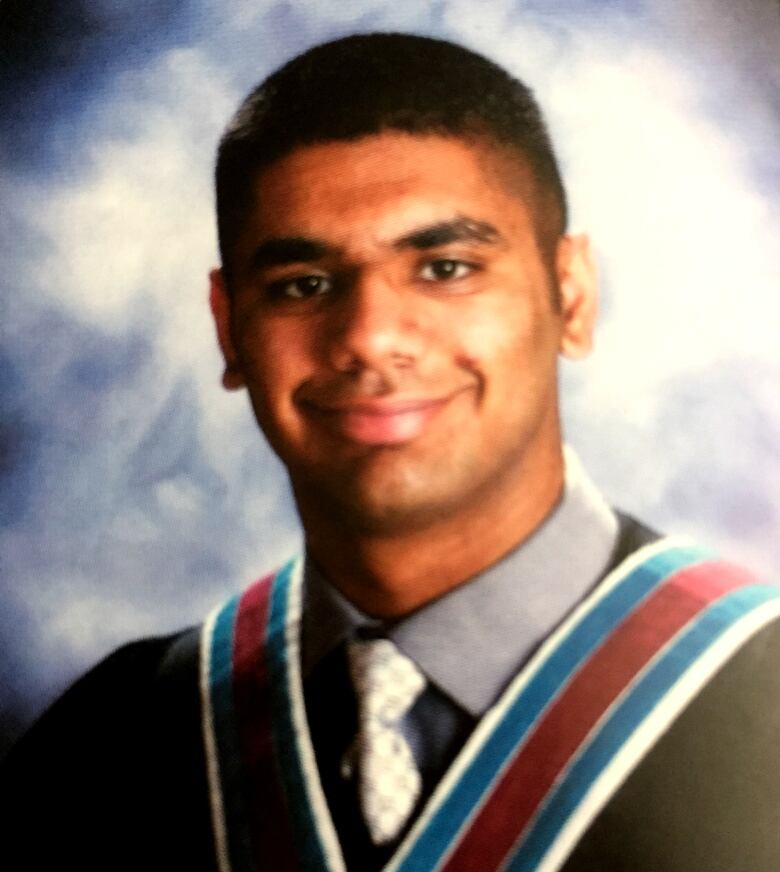

She is the mother of one of eight menpublicly identifiedas victimsor intended victimsof shootings that are terrorizing her community.

But she's afraid to admit it.

"I have to say he's not my son," she says."I feel really, really ashamed."

- Homicide victim's family say he wasn't gang member

- Surrey RCMPrelease photos of unco-operative victims

CBC News agreed not to identify the woman, whosays she fears for her family's safety after Surrey, B.C.,RCMPtook the unusual step ofreleasingphotographs of men who are allegedlyrefusingto co-operatewith investigators trying to solve aspree of nearly two dozen shootings.

Further risk?

In addition to the eight victims,RCMPhaveidentifiedfive other menbelieved to be involved in the shootings.

Civil liberties advocates say the case raises questions about the balance between public interest and privacy.

"What's important in this case is the implication of sharing these images for not just the privacy of the victims, but also their safety," says Laura Track, counsel with the B.C. Civil Liberties Association.

"Sharing their images widely and publicly, we're concerned, could put them at further risk."

'A stamp on his forehead'

The woman says her son's car was shot, but he wasn't injured. She admits she doesn't know exactly what he might be involved in, butsays he's not a killer.

"I want to make sure the public is safe, but I'm not sure this is the way to do it," she says.

"He's a victim, but the way it has been worded, he belongs to a gang. They've put a stamp on his forehead,saying: 'You're in a gang.' That's totally wrong."

The RCMParesubject to the federal Privacy Act, which limits the release of personal information bygovernment agencies.

Exceptions includesituationswhere disclosure would clearly benefit the individual, or where the public interest in disclosure outweighs the invasion of privacy.

Public's right to protection

The turf war has resulted in 22 shootings and one homicide in Surrey and Delta inthe past six weeks.

But police say they're getting answers from the victimslike, "The bullets fell from the sky" and "I will take care of it myself."

"If a person is aware of who committed the violent crime against them and are unprepared to share that with us, we need to take the steps to protect the rest of the public," says Sgt. Dale Carr.

"The rest of the public have the right to not have shots fired in their neighbourhood, to be living in fear, to be worried about getting hit with a stray bullet. That right also exists out there."

Carr says they chose to seek information through the release of photographs, "because for us to be able to simply describe these males would not have accomplished the task that we needed to do."

Track notes a recent controversy in which Lower MainlandTransit Police issued a public plea for a sexual assault victim to come forward:they identified herethnicity, estimated age, hair colour, height and clothing.

Some women's groups claimed the detailed description possibly identified the woman, who might have valid reasons for not wanting to go through the trauma of making a complaint.

"The issue is a victim's right to anonymity and to privacy, if that's the choice that they take," she says.

"There may be very compelling reasons why a victim of crime might not come forward to police in a sexual assault context. There may be very compelling reasons why the victims of these cases are choosing not to come forward."

The power of an image

Canada's privacy commissioners recently called on police forces to addressthe balance of privacy and law enforcement in relation to the increased use of body cameras.

Wilfrid Laurier University associate professor Christopher Schneider, who studies technology and policing, says images havefar greater impact than names or verbal pleas.

"When you look on social media, a lot of the material thatare shared are pictures or images. You can share them on Facebook, you can share them onInstagram," he says.

But what happens to the victims once the case is closed?

"That's the huge problem. That's the privacy concern," Schneider says. "The internetnever forgets and the internet is unforgiving."

Carr says that if any of the identified victims are worried, there's a simple solution: talk.

"If he's got those concerns, and he has information that would help us advance the investigation and put the people who are after him in jail, then his safety would be paramount."

Meanwhile, the man's mother claims she's struggling to get answers herself.

But there's only so much anyone can tell her about her adult son for privacy reasons.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)