For Alberta, the day of fiscal reckoning has arrived

Provinces economy and budget can recover, but it will require hard choices

This column is an opinion from Trevor Tombe, an associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary.

In his televised address on April 7, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney did not mince words: Alberta is "facing not one crisis, but three."

The health and economic shocks from COVID-19 are massive, but they are shared by many around the globe. The collapse of oil prices, however, presents a third crisis that is partly of our own making.

"Alberta's budget deficit this year may triple from $7 billion to almost $20 billion," the premier said, adding that we will soon face "a great fiscal reckoning."

While there remains a uniquely high degree of uncertainty right now, and both the premier's statement and my high-level analysis in this article should be seen in that light, there is no getting around the significant challenge that awaits.

But there are options. Alberta's economy and our budget can recover, but it will require hard choices and cross-party compromises that we too often resist.

Taking stock

First, we should appreciate our current predicament. A $20-billion deficit is plausible.

Consider three major sources of Alberta government revenue:

-

Income and Other Taxes: We were hoping for $23 billion this year. But a contracting economy and income losses from low oil prices together suggests nominal GDP may fall by 15 to 20 per cent. This means lower revenues possibly $4 billion lower.

-

Investment Income: Alberta has large savings that generate returns. We were hoping for $2.6 billion this year, butas anyone who has checked their RRSP recently knows, we're more likely to lose money this year. During the financial crisis we lost $1.9 billion. Today, losing $1 billion is possible, which would lower government revenue by $3- to $4-billion relative to our previous estimates. (Of course, how the market will performover the coming months is not known, and the government might book recent losses in 2019/20 instead.)

-

Resource Revenues: Alberta chooses to rely heavily on resource revenues to fund public services. And when energy prices fall, so do revenues. The government was hoping oil would fetch $58 per barrel this year; today it's less than $20. So instead of the $5.1 billion we were hoping for, we might see $2 billion (or less).

We could keep going, but these three items alone put us on track for a revenue hit of $11 billion. Add additional health-care spending of at least $500 million (possibly more) and other costs, and we're almost at a $20 billion deficit already, up from the original $6.8 billion.

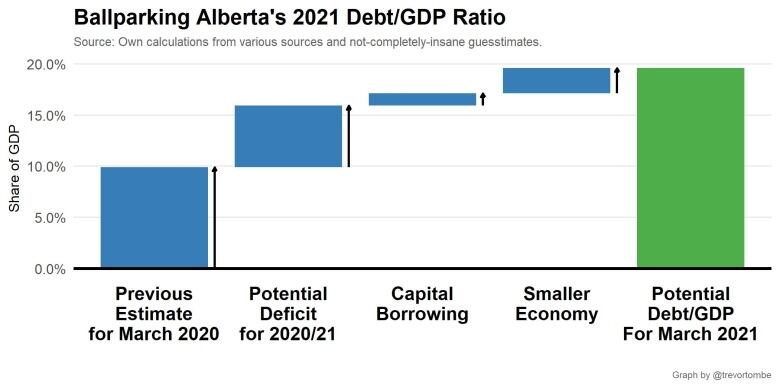

Combined with borrowing for capital projects and a smaller economy, we could be looking at a 20 per cent debt-to-GDP ratio double our current level.

This short-term challenge is manageable, to be sure, and Alberta would remain the lowest-debt province.

The trouble is, these fiscal challenges will continue for many years.

Our fiscal reckoning will last years

Oil prices are not projected to bounce back anytime soon.

Current futures prices are roughly $20 to $30 per barrel lower than government forecasts by 2022-23. And to balance the books that year, the government was hoping for $8.5 billion in resource revenues. This is no longer in the cards. Not even close.

Budget 2020 provides some clues of how bad it might be.

The budget reported "high" and "low" economic scenarios for 2022-23 that, roughly, corresponded to a $20 per barrel swing in oil prices (see page 73 of the budget). Such a swing may lower income tax and resource revenues by nearly $9 billion, they report.

The shock we're facing today is slightly larger, so instead of a modest surplus by 2022, we may see a deficit of more than $9 billion.

Let that sink in. After four years of significant spending restraint, we're on track for a larger deficit than the one we started with.

This is our fiscal reckoning. But, luckily, there are options.

Getting out of the fiscal hole

Let's start with the government's current policy: a freeze in program spending.

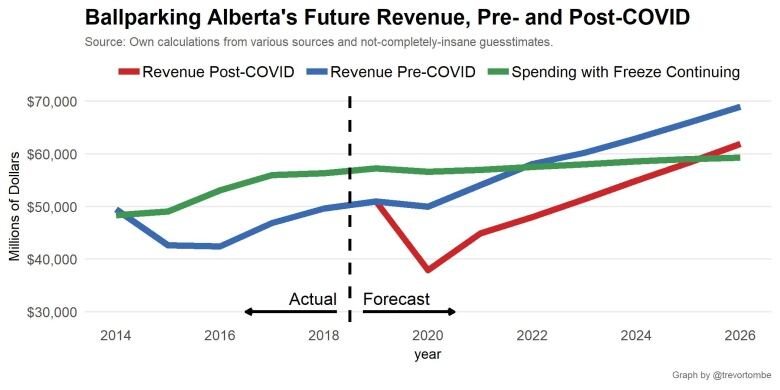

Without going into details, I updatedmy own model of Alberta's budget to reflect most of what we know today from publicly available sources and display the results below.

The government's current fiscal policy suggests we'll balance four years later than planned: 2026 instead of 2022.

This is less than ideal.

Alberta would see $140 billion in taxpayer-supported debt, with interest costs of nearly $6 billion per year or roughly triple our current amount. And, since prices and population will continue to grow, a freeze is effectively a nearly 30 per cent reduction in the inflation-adjusted per person level of spending. This would require a deeper reinvention of public services and is roughly double the government's previously planned restraint.

But there isanother side to the budget: Revenue.

Consider a broad-based and efficient source of revenue like the sales tax. Alberta already has one, of course: it's called the GST. Except the federal government gets all of the revenue.

Alberta could, if it wanted, raise the GST from its current five per cent and keep the incremental revenue (this is known as a harmonized sales tax, or "HST").

If, starting next year, Alberta gradually phased in a four-point increase to the GST (which would be lower than any other province), then we'd be on track to balance the books by 2024. That would mean only two additional years of frozen spending, and would avoid roughly $20 billion in additional debt.

Of course, there are other revenue options.

Some might prefer higher income taxes. Adding one point to all income tax brackets could add around $1.5 billion to revenues.

Some might prefer pausing the corporate tax cut. This would add around $500 million.

Others might suggest Alberta take back carbon tax revenues from Ottawa. Once it reaches $50 per tonne, that would be $2.2 billion to Alberta and if we kept rebates to lower income households, it might net $1.5 billion.

Whatever the tool, to balance by 2024 with frozen spending requires we raise total revenue by roughly eight per cent. And if, after 2022, we allow spending to keep pace with population and inflation, revenue would have to rise by 15 per cent.

Even with such increases, Alberta would still enjoy the lowest taxes in the country by an extremely wide margin but it would be challenging nonetheless.

Can Ottawa help?

All provinces are facing revenue shortfalls and spending pressures. And Ottawa will likely offer support. But it matters less than you might think.

Ottawa could cover some (or even most) of the direct COVID-19 related expenditures by extending the disaster assistance program to cover pandemics (it currently does not). If Canada supported provinces with funding in line with what the United States delivered for states, for example, Alberta might see over $2.5 billion this year.

Ottawa could also cover a share of revenue declines through a reformed Fiscal Stabilization Program (which Alberta has long demanded). If it fully acceded to Alberta's request for reform, Alberta might see $3 billion more this year.

There's a strong case to be made for such support, since it's cheaper and easier for the federal government to borrow and smooth out shocks like COVID-19 than it is for provinces. There are also many options for reform, from removing the current cap on payments to more fundamental reform.

But even though these dollar amounts are large, and helpful for provincial balance sheets, such federal support would barely nudge Alberta's daunting longer-term trajectory.

Alberta's fiscal reckoning is of our own making. We cannot look to Ottawa to fix it.

It's time to change course

There are real political challenges with spending restraint and new taxes, to be sure. And there's no easy option. But cross-party compromise and a whole-of-budget approach to tackling this challenge is the best way forward.

Government and opposition parties must both re-evaluate their approach to fiscal policy. And Albertans must give them space to do so.

After the dust from the health crisis settles, we'll need to have an open and honest discussion about our budget and our future. Our fiscal reckoning may look bleak, but we have options. We just need to choose wisely from among them.

This column is an opinion. For more information about our commentary section, please read thiseditor's blogandour FAQ.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)