Special education funding sparks First Nation human rights complaint

Mississaugas of the New Credit head to tribunal over special education funding

A First Nation near Hamilton is moving ahead with a human rights complaint against the federal government over funding for special education for children who live on-reserve.

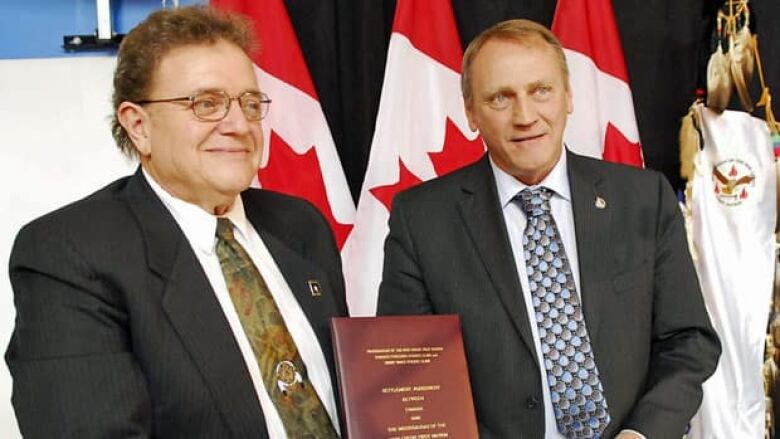

Mississaugas of the New Credit Chief Bryan Laforme said his First Nation doesn't get enough funding "to cover the needs in our own school."

The federal government funds schools on reserves at a rate of about one-third less per student than provincial schools receive, a disparity that hits especially hard when it comes to helping children with special needs, Laforme said.

"We're the First Peoples," he said. "We shouldn't be treated as second-class citizens."

Laforme said children from the Mississaguas of New Credit who have special education needs have to leave the community to get the services they require.

Child welfare funding concerns

No date has been set for the Mississaugas of the New Credit complaint to be heard, but a national organization is before the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal this week, arguing that the federal government discriminates against First Nations in funding for child welfare.

The complaint, first filed in 2007, alleges the federal government has a "longstanding pattern" of providing less funding for child welfare services to First Nations children on reserves than it does to non-aboriginal children living off reserves.

- Read:Ottawa fights charge it discriminates against aboriginal kids

- Watch:Q and A with Cindy Blackstock

- Listen:Thunder Bay man seeks accountability for lost childhood

The Harper government argues it has increased its funding for child and family services by 25 per cent, to more than $600 million annually.

But the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada estimates that First Nations children on reserves receive about 22 per cent lessin funding for child welfare than children living anywhere else in Canada.

"This case was filed as a last resort after successive governments have failed to implement the solutions that would help First Nations children stay safely in their families," according to the society's executive director Cindy Blackstock.

Laforme said he is a strong supporter of Blackstock and her fight, adding that inequalities in funding for child welfare exist in First Nations communities across the country, including his own.

"There has been a disparity for a long, long time," he said. "The time has come for Indian Affairs to step up, to make sure they're treating us the same as anyone else."

Former auditor general Sheila Fraser estimated First Nations children were eight times more likely to be in care than other Canadian kids.

An Ontario government report from 2011 showed aboriginal people make up about two per cent of the population, but between 10 to 20 per cent of the children in care.

The Mississaugas of the New Credit have an agreement with the children's aid society in Brantford. Laforme said it's to ensure children aren't taken away from their parents over concerns that are related to poverty rather than neglect.

Chief 'furious' over past attempts to remove children

He said his First Nation has even had to fight with child welfare agencies from across the border.

"A few years ago we had people from a children's aid society in Buffalo up here trying to take our kids away," he said. "I was just furious."

That anger has historical roots. The so-called Sixties Scoop saw an estimated 16,000 First Nations kids in Ontario taken away from their communities in the 1960s and 70s, and adopted out to non-Aboriginal families.

Laforme said the implications of winning a human rights complaint aren't clear, since the federal government often appeals legal losses.

The First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada case is expected to take several months.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)