Damage of residential schools revealed through tears of 3 macho men

I first heard about Indian residential schools 33 years ago, and I have a unique experience to share that I hope might convince others that even the strongest of the strong will always have difficulty coping with what happened to them in the past.

I was supposed to join three of my buddies, big macho guys, for a beverage during the intermission of a play I had been hired to write at the World Assembly of First Nations.

Felix, Dutch and George, all alumni of rough and tumble Saskatchewan Junior A hockey teams, didn't show up.

At first I thought it might be because they each owed me a sawbuck for a bet on a Bombers-Riders game.

Later, I learned it was because they had been scrambling for a place to hide a flood of tears they couldn't keep from streaming down the cheeks of their macho, jock faces.

in Deo

Felix, Dutch and George had been watching a play called in Deo at the Saskatchewan Centre of the Arts in Regina (also known as the Conexus Arts Centre) during the World Assembly of First Nations in 1982.

The play is a musical that presents the story of First Nations in North America before the arrival of Europeans, the impact of colonization, and a look to the future in which First Nations can combine the modern tools of Euro-Canadians with the traditions and culture of First Nations to build a new world.

There are no words spoken in the play. The traditional way of life is presented through a "Sunrise Ceremony," "Hunting Song," "Shield Dance," "Hand Game Song" and a lullaby.

The arrival of the Europeans and the building of a new world is presented through classical music, opera, ballet, folk, blues rock and jazz, all of which takes place in a representative Indian village from the past.

Untold truths

There really hadn't been much public discussion about the Indian residential school experience back then. It was a dark secret that hurt or shamed the people who were involved with it too much.

But the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations had told me to consult with elders to ensure the play was accurate and culturally appropriate.

The elders responded with enthusiasm, and many expressed a wish that what happened at boarding schools could be dealt with in some way.

I had never heard about these boarding schools and I didn't fully understand the impact this experience had on First Nations people (this is modern Canada, not some Dickensian novel, right?).

Symbols of hope

The play was meant to be hopeful, so we crafted it to be subtle and symbolic. The last thing we wanted to do was preach or lecture or create guilt feelings amongst the mainstream audience that would be in attendance.

So we included a couple of scenes that were by no means as graphic as the horrific testimony the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has heard.

The residential school scenes were designedas a turn aroundto the dominance Euro-Canadian culture was taking over indigenous people, and we presented those scenes just before the intermission.

The Indian village experiences the haunting chants of a "Death Song" as a huge cross dominates the stage. As the adults in the village try to deal with this strange, new spiritual presence, their children, dressed in buckskin, are led away, singing :Jesus Loves Me" in Cree.

Folk artist Shingoose sings:"The elders are the teachers and they share their wisdom with the gifts of song and the gifts of legend. They said it wasn't right and we had to see the light. And now from the deadness of the boarding schools."

The children return dressed in boarding school clothes singing "Jesus Loves Me" in English.

Little dancer

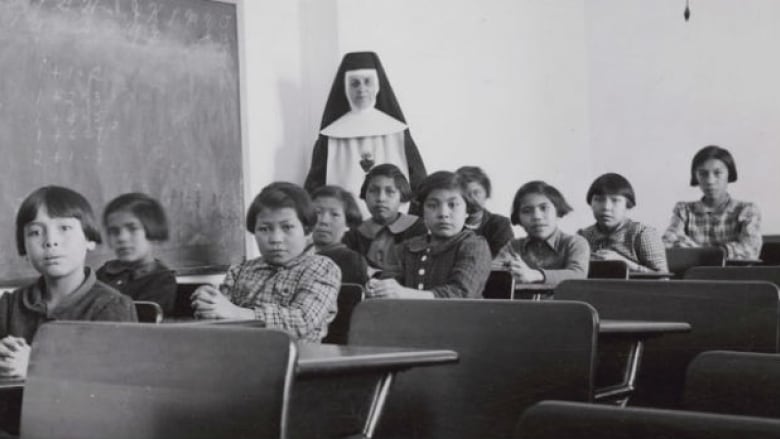

The children sit down at desks and begin to study from text books when a young, traditional dancer appears and begins to dance, weaving his way in and out of the rows in the classroom.

The more the little dancer, in full native regalia, tries to dance proud and strong, the more the children bury their head in their text books, until the young traditional dancer ends in a corner of the classroom, and bows his head in despair.

Then, Boom! The house lights come on for an intermission.

Unfortunatelyfor Felix,Dutch and George, their heads were bowed in despair, too. All of the memories of their residential school experiences had come flooding back.

They carried those experiences with them through to adulthood, and it all came out in one huge, emotional outpouring that even big, macho jocks like Felix and Dutch and George couldn't contain.

True impact of residential schools

And when I saw these tough guys react in this way, I learned abut the true impact of the residential schools. This is why we cannot file the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's report on a shelf.

We are only moving on to the next stage. Reconciliation. Dealing with the multi-generational impacts. If you think people should just "get over it," try telling that to Felix, Dutch and George. And you might just find out how thick the skin on their knuckles is.

Don Marks is a Winnipeg writer.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)