Quebec doesn't track outcomes of police abuse complaints from Indigenous people

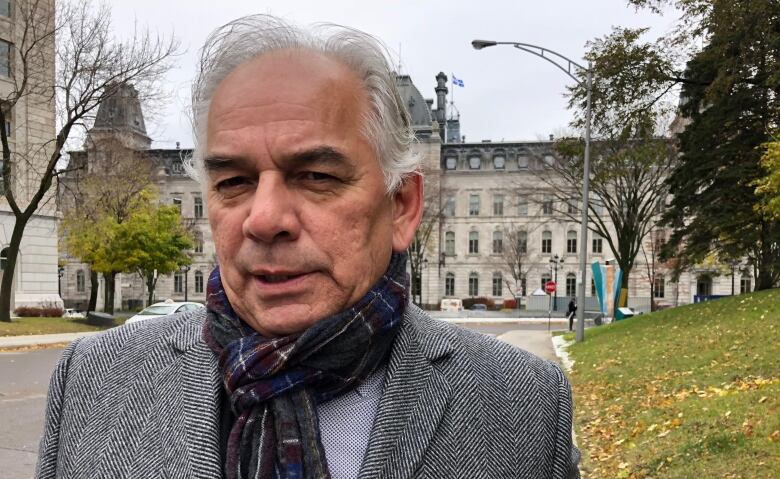

AFN regional Chief Ghislain Picard hopes Viens Commission report, to be released Monday, will address problem

Ghislain Picard hopes Jacques Viens, the retired Quebec Superior Court judge who heard hundreds of stories of discrimination and racism from First Nations and Inuit people in the province, will address a lot of problems in his report, to be released Monday.

High on that list is tracking what happens to complaints fromIndigenous people allegingabuse by police, said Picard, the Assembly of First Nations regional chief for Quebec and Labrador.

"That data is critical," said theInnu leader. But CBC News has learned it can't be had.

All eyes will be on Val-d'Or, Que., next week, when Viens presents recommendations from his $17-million inquiry. But they wouldn't be, were it notfor the 93 men and women most, but not all, Indigenous who lodged complaints about the way they'd been treated by a police officer in the province.

It began with 14 allegations of sexual assault by police officers: complaints filed in the months following an explosive report by Radio-Canada's Enqute in October 2015, in which Indigenous women in Val-d'Or alleged they'd been harassed and mistreated by some provincial police officers stationed there.

- Aboriginal women's claims of police sex abuse under investigation

- More Quebec Indigenous women break their silence about police abuse

Between April 2016 and June 2018, another 55 men and womencame forward with their owncomplaints, from all across the province.

Crown prosecutors have yet to reveal how many of those 55 cases involve allegations of a sexual nature.

So to date, there is no way to know if Indigenous women are more or less likely than women in the general population to be victims of sexual abuse by police.

48 officers investigated for alleged sexual offences

CBC has learned through an access to information request that 48 police officers in Quebec have been investigated for committing an infraction of a sexual nature on the job since 2016.

The Public Security Ministry, which publishes information annually about criminal allegations involving police officers, has refused to divulge how many of the alleged victims are Indigenous.

So has the Bureau of Independent Investigations (BEI), the specialized police force that investigates incidents in which a firearm was discharged or someone was hurt in the course of a police operation.

In September 2018, the BEI was given the exclusive mandate to handle any allegation of sexual assault or abuse by a police officer. It provides information about the number of overall complaints, categorized by region and police force, and it makes public the number of Indigenous people who have laid complaints against police.

However, itwon't say how many Indigenous complaints are sexual in nature nor will it reveal howmany of those same complaints BEI director Madeleine Giauque dismisses internallyand how many complaints the BEI hands over to the Quebec Crown to determine if charges should be laid.

Picard doesn't understand why the BEI reveals other data, such as how many Indigenous complaints it handles compared to the number of complaints from non-Indigenous Quebecers, but notthe outcomes of those investigations.

"If you consider it at the outset, then eventually just mix all the complaints together at the end of the process, what is the purpose?" he asked.

No Indigenous investigators

Picard said the BEI has made efforts to improve how it deals with Indigenous people, by hiring an Indigenous liaison officer to train investigators about cultural differences and to help spread awareness of the BEI's role in First Nations and Inuit communities.

However, hesaid, the BEI has to do more than hire a single person to help repair the fractured relationship between Indigenous people and police, which goes back decades.

He said First Nations and Inuit people need to see themselves represented among the investigators to believe their experience will be properly understood.

"Every effort has to be made in order to establish that trust," said Picard.

In its annual report released Wednesday, the BEI states 8 of the 44 members of its investigative staff are from various ethnocultural communities. None is Indigenous.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)