22-year-old Yukoner reunites Haitian 'orphans' with parents

'Little Footprints, Big Steps' offers safe places for children to receive care, tracks parents down

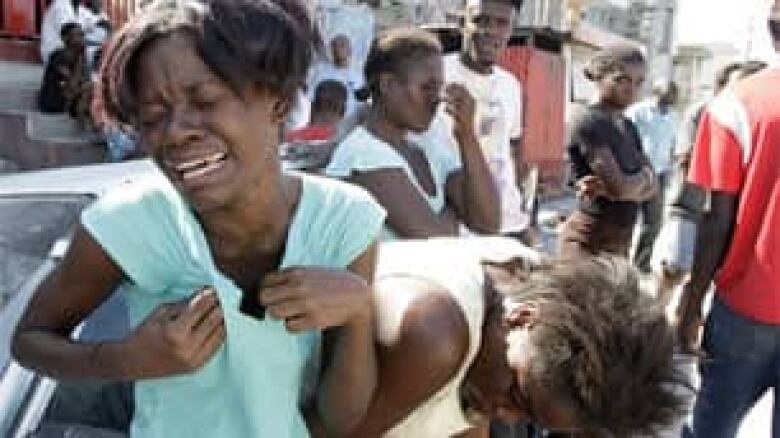

Morgan Wienberg, a slight22-year-old from Whitehorse,was only 18 when she joined the wave ofvolunteers who flew to Haiti to help out after the catastrophicearthquake in 2010.

Unlike most volunteers, she's nowreturned, putting off amedical career to fulfil what she calls a life mission torescue abused Haitian children exploited by unscrupulousorphanages.

"I am flabbergasted by her story. It's simply outstandingwhat she is doing, and nothing fazes her," said Alison Thompson,an Australian nurse and veteran relief worker who ran a camp forearthquake victims in Haiti and now runsrape clinics there.

Wienberg was living in Whitehorsewhen her plans to study medicineat McGill University took a detour.

She had considered spending the summer working with animalsor children in Africa, but quickly signed up as a volunteer toteach English to earthquake victims and help in a prostheticslab.

"I had never really thought about Haiti. The earthquake drewme to thinking it was the place I could make a difference," shesaid during an interview in Miami where she was overseeingmedical care for one of her charges.

Starvation and Beatings

In Haiti Wienberg also volunteered at an orphanage. Appalled bythe conditions, she quickly discovered that almost all thechildren were not orphans, but were being used to milk donationsfrom unwitting charities, including American churches.

"There were 75 children, all starving, lying in vomit anddiarrhea," she said. Beatings were common for petty infractions;a deaf boy was abused constantly.

When groups of Americans visited with suitcases of toys andclothes, the owner made sure the children were washed andclothed. They never received the donations, which were sold.

"The real turning point was when I realized the children allhad families," said Wienberg. "They were there because theirfamilies were so poor they couldn't afford to look after them."

Wienberg discovered that the orphanage owner recruitedchildren on trips to impoverished rural areas where parentsoften were willing to give up their children for the hope theymight get a better life in the city, and perhaps an education.

"Many orphanages in Haiti are primarily a business," saidWienberg. "They use the children to make money from foreigners."

She gathered evidence and went to the police and Haiti'ssocial services institute to report the abuse.

Legitimate children's homes exist in Haiti, such as NPHInternational, which operates a children's hospital inPort-au-Prince and a chain of orphanages across Latin America.

registry of the 725 orphanages and child-care centres.

Of these, 40 have already been shut down, including the orphanagewhere Wienberg worked, though officials say the social servicesinstitute, which has a staff of 200, lacks the resources toproperly monitor abuses. So far there are no reliablefiguresfor the total orphan population.

Terre des Hommes International Federation, a Europeanumbrella group dedicated to children's rights, is working with

UNICEF and the Haitian institute to replace orphanages with anationwide host-family program. It seeks to prevent separationby helping the most vulnerable parents find a sustainable sourceof income, such as training women to sew and helping fishermenwith nets and boats.

The initiative also includes a "family tracing andreunification" plan to help remove children from orphanages andplace them back with their parents.

After Wienberg quit the orphanage, she decided she could notwalk away from the children. Back in Canada she worked threejobs to save enough to return to Haiti.

"Every day I was working to get them medical treatment andtrying to close (the orphanage) down," she said. Often she hadtrouble sleeping, remembering she had shared the floor with kidswho had no beds.

From Shyness to Safe House

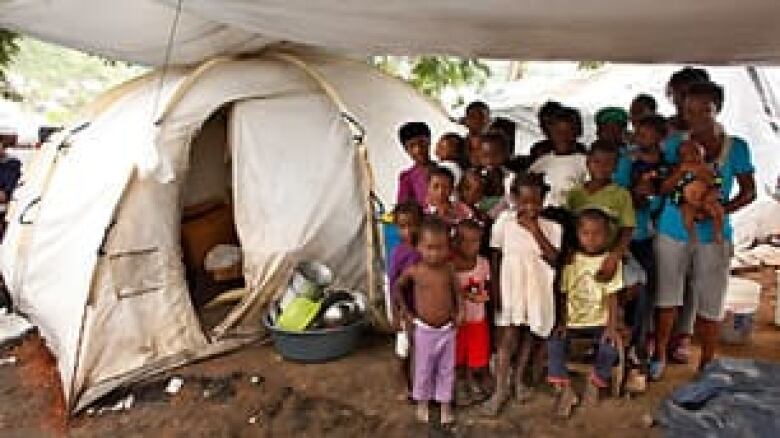

With that money and what she had put aside for university,Wienberg set up her own charity in late 2011: Little Footprints,Big Steps offers safe places for children to receive care, whiletheir parents are traced.

Morgan's mother, Karen Wienberg, 57, serves as chairman ofthe board. A Canadian civil servant in Whitehorse, she organizesadditional fundraising.

So far Morgan has rescued 86 children and is helping theirfamilies provide for them at home, while also paying to educate156 children. She herself currently looks after five boys and five girlsat one of two safe houses in the southern city of Les Cayes.

One boy, Yssac Jeudy, was 12 and illiterate when she rescuedhim from the streets. Known to his friends as "Big Cheek"because of a tumor growing beneath the right side of his face,he is now in Grade 2and at the top of his class. Wienbergbecame his legal guardian this year in order to bring him toMiami for surgery (the tumor was benign).

"Our focus now is on helping the children stay with theirparents and build stable lives," she said. That involves teaming

up with other charities to build houses and help with vocationaltraining.

The charity has an operating budget of $175,000 and shunsluxuries, such as a car, preferring the money go for food,education and medical care. Only eight local staff draw asalary.

Wienberg, who taught herself to speak fluent Haitian Creole, travels everywhere on public transport, despite the five hoursby bus that separate Les Cayes from the capital, where she mustfrequently go.

"Morgan doesn't have any interest in material things. She isprobably the most incredible person I have ever met," said SarahWilson, a Canadian paramedic in Ontario who co-founded LittleFootprints with Wienberg after they met in Haiti.

Once painfully shy, Wienberg has since delivered a TEDxaddress (a freely licensed version of the more global TED talks)at McGill in Montreal, and last year she was invited to speak atthe United Nations Youth Assembly in New York.

Some of her admirers worry about the risks she runs inHaiti. "All my friends who are nurses have been assaulted or raped at one point," said Thompson. "But her kids really loveand protect her. She has won the respect ofthecommunity, andthat counts for a lot down there."

Karen Wienberg doesn't worry about her.

"A mother's job is to open every door for your children sothey can find their passion," she said. "If I had a child sitting on the couch I would worry more."

Despite her present involvement, Morgan hasn't necessarilygiven up on medical school. "I spent all my savings," she sayswith a laugh, "so I'd probably need a scholarship."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)