Parents of children with disabilities worried about access to specialists if COVID-19 outbreak hits

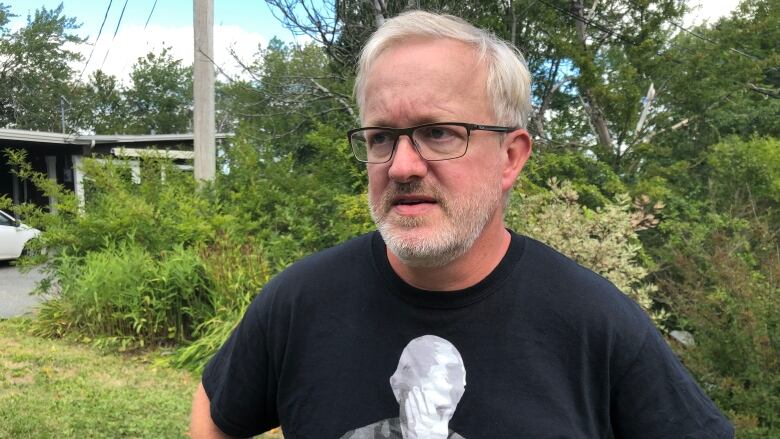

Corey Slumkoski says he's not confident in the Department of Education's plan if schools are shut down again

Parents of some Nova Scotiachildren with disabilities say they're worried about what will happen to their children's learning plan if they have to leave the school due to a potential outbreak of COVID-19.

Among those worried is Corey Slumkoski, whose seven-year-old daughter, Quinn, begins Grade 1 at Rockingham Elementary in September. Quinn has Downsyndrome and relies heavily on the support of the speech language pathologist assigned to her school.

"We don't know if we pull her outif she will still have access to this on a regular basis," Slumkoskisaid. "And we also don't know in the disability community, as a whole, if other people have access."

Quinn is non-verbal but has been making strides toward better communication with the help of an iPad loaded with speech language pathology software. Slumkoskisaidhe and his wife marvel at her progress.

But they say without a trained specialist to guide her learning, they're stuck. They hope she'll learn to communicate verbally eventually, but they don't have the skills to make it happen.

"Our concern is that if she's pulled out of school or if the schools close, that she'll essentially be stuck where she's at,that we won't be able to push the envelope," he said."We won't be able to help foster her ongoing development."

Slumkoskimade the decision to send her back to school on the direction of their doctor even though her immune system is at the low end of normal. Typically, Slumkoskisaidwhen the flu or common cold are making the rounds, his daughter will end up spending about three months at the IWK. She'd be on high-flow oxygen for about half that time.

Ironically, during a global pandemic, this is the first year she didn't have to spend time at the IWK. Like many parents, they believe the best place for her is in a classroom. But they're also acutely aware that Quinn would be among the first to resort back to homeschooling, should there be any spread of COVID-19 at her school.

Last Wednesday, Dr. Robert Strang, Nova Scotia'schief medical officer of health, explained his reluctance to work out and present detailed plans for any hypothetical scenario.

"There's no cookie cutter model that we follow, despite what people are asking for," Strang said.

"The nuances of every situation and the context dictates our response."

On Monday, CBC News asked the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development if it could assure parents like Slumkoskithat his daughter's speech language training would continueif she was forced back into homeschooling. Itdeclined an interview and instead provided a statement.

The department said it recognizes "a very small number" of children won't be able to attend school and said theywill receive learning materials at home.

"In these situations, schools will also work with parents to ensure those who require access to additional supports, like speech language pathologists, have options for continued access," said the statement. "Those discussions will take place between families and their school."

The department said people concerned about a family member who is immunocompromised should contact their health-care provider for advice.

The assurance of "options for continued access" doesn't provide much comfort for Allison Garber, the mother of a boy withautism.

"My expectation would be that there is a plan in place," she said. "Unfortunately, our families have not seen that plan."

Garber saidshe's not convinced the appropriate supports will be available in a school setting let alone at home.

"Right now, my family and many other families are sending their children to school, not knowing if the supports that they need to access a fair and equitable education are going to be in place," she said. "And that's a human rights issue."

Slumkoskisaidthe province's approach "is to plan for the best and hope for the best."

"Instead,I think they should be planning for the worst. They should be planning for the possibility that schools will have to shut down and make arrangements to provide services to students who need them."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)