'I played the tanned white girl role,' says Mtis woman who took years to acknowledge, embrace her heritage

Connecting with her Indigenous roots has now helped Jenna Tickell work through the loss of her mother

Jenna Tickell got used to playing the "tanned white girl" role until she was 23 years old.

It wasn't until she took a class on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girlsin university that the Regina womanknew she had to dig deeper into her roots and face who she really was. The class she took explored the historical reasons why Indigenous women are targeted and why identity is so important to Indigenous people.

When it was Tickell's turn tointroduceherself, she knew it was then she had to share her truth.

"I stood up and I said:'I am Mtis. I am Jenna.'"

She said"it was a very powerful moment for me. But the fact that that happened when I was 23? That says a lot ... because I didn't feel comfortable."

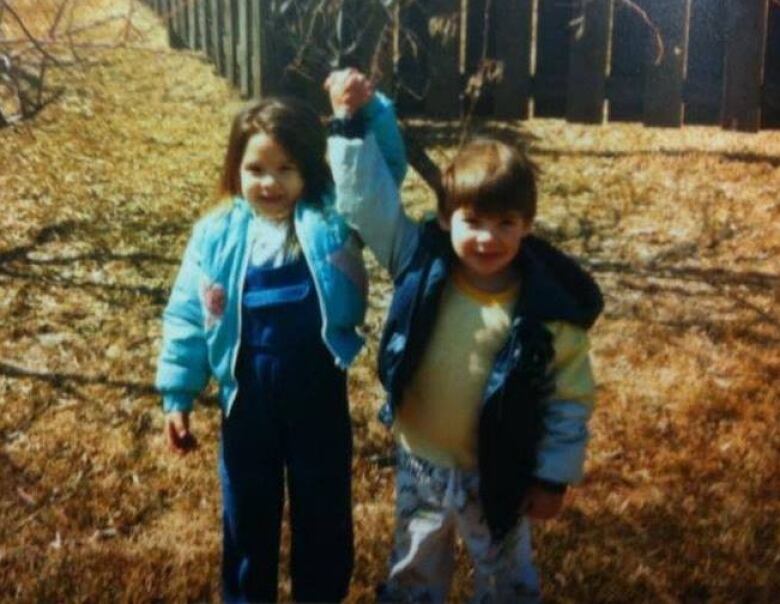

That unwillingness to share her identity went back to when Tickell wasa child playing with her best friend.

"I let her know that I was part Indigenous and her mother was astounded, and she wouldn't let me play with her again," said Tickell.

"I never saw that friend again. I was only five."

She said she would carry this difficult lesson with her until she was an adult.

"At a very young age I learned, 'This isn't good. I can't tell people this.'"

But growing up, she never understood why being Indigenous was a "bad thing."

"I just knew there was a part of myself that I couldn't tell people aboutor they wouldn't be friends with me," she said.

After that, Tickell said she "kind of just played the tanned white girl, and Inoticed the difference in how Iwas being treated in high school as opposed to the way my brother was being treated."

"Because he was a little bit more darker skinned, it was more obvious," said Tickell, adding that her brotherhad an "Indigenous last name." She said he was treated differently by his classmates and teachers.

Tickell'sMtisheritage is onher father's side of the family. Herroots come from the Crooked Lake area and theCowessessFirst Nation in Saskatchewan. She saidher grandmother speaksMichifand can trace her lineage back to the Red River settlement in what is now Manitoba. But because hergreat-grandmother was a residential school survivor, her grandmother chooses not to follow Indigenous spirituality, instead choosing to practise Catholicism.

Tickell'smother isScottish and Irish.

With the help ofelders andprofessors,Tickellhas now embraced Indigenous ways in her life andher research as a Master's candidate at the University of Regina. She has attended solidarity walks, protests, feasts, ceremonies, and runs Project of Heart, an educational event held at the university that teaches administration and students about residential schools.

Still, she faces opposition when she tells people about her Mtis heritage.

"AsIndigenous women, we have to qualify ourselves. It's not enough to say, 'I'm Indigenous, I'm Mtis.' The next question that always follows up is:'What makes you Mtis?'"

Looking back at her high school pictures,Tickellcan see how the lack of identity is reflected back to her.

"My mom took it," she said, referring to one."You can see in my eyes that something is missing from deep within me."

Things have now changed.

Last fall, Tickell lost her mother to lung cancer. She said with the help of elders she has been able to grieve through traditional ceremony.

Her partner, who is non-Indigenous, told her he would do anything to help her in this process. She asked him to cut her hair.Tickell said hewas taken aback as she had really long hair at the time.

"He's moving his hands in and out and then he finally cut it. And he was holding the braid in his hand and he looked at me with his mouth wide open ...and then I wrapped it in a white cloth," she said.

Tickell said she went through with other ceremonial protocol after cutting her hair. Her siblings have done the same thing so they can heal together even though they liveacross the country from each other.

"I'm going through one of the biggest griefsI'll ever go through," she said as she started to hold back tears.

Now, she gets solaceby having trust in the Creator and praying.

And as for her identity?

"I can qualify it and now I'm not afraid to say it."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)