Regina researcher part of new study that shows it's 'virtually impossible' to dispute climate change

New database shows temperature records going back as far as 2,000 years

A Regina-basedresearcheris one of nearly 100 scientists hand-pickedfrom around the world to be part of a new study that showsthe planet is indeed getting hotter.

David Sauchyn is a senior researcher at the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative and professor of geography at the University of Regina.

He's one of a handful ofCanadians whose climate research has been used to create an internationaldatabase of historicaltemperature records some going as far back as 2,000 years so scientists could have a better ideaof what the earth'snatural temperature wasbefore humans started burning fossil fuels.

- Climate change researchers cancel expedition because of climate change

- Scientists study tick populations against backdrop of climate change

- Climate change is making Antarctica greener

The major finding? That the planet's temperature was declining over the last 2,000 years until 150 years ago when that trend did an about-face, and temperatures started rising rapidly.

"It just adds to the large body of scientific facts that confirm, that verify that the climate is warming at an unusual rate," he said of the study.

"We haven't discovered anything new, it's just that we presented such a conclusive set of facts that it's virtually impossible to argue anything else."

The database is published on an online journal that allows open access to data deemed important to science. It was created as part of global research initiative on climate trends.

Looking beyond weather

Unlike other studies that use weather to study climate, this one examines climate by looking at natural life,such as mineral orcoral growth, orin Sauchyn's case, the growth of trees.

"All of these natural phenomenon are sensitive to temperature and so we can actually determine what the temperature was when these things were growing 2,000 years ago or 1,000 years ago," he explained.

He said he was asked to participate because for the past 25 years, he and students have collected wood from across the Prairies.

As a result of that work, Sauchyn was able to provide temperature records for two sites in the Canadian Rockies from more than 600 years ago.

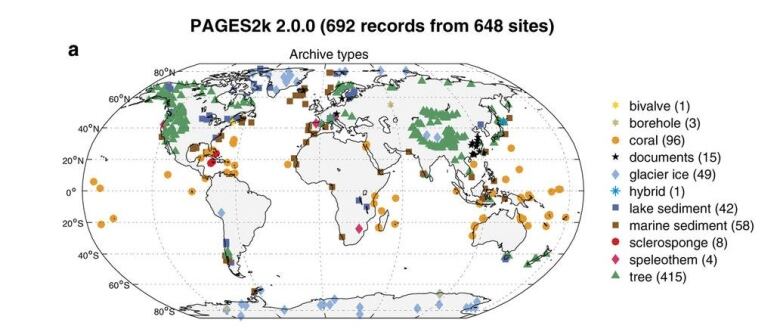

The database includes 692 of these temperature records from 648 sites around the world, includingoceans.

He said similar studies of this nature have been done in the past, but nothing onthis scale.

More data, better conclusions

Sauchyn explained only looking at climate by studying weather leaves a short history.

"Weather stations have only existed around the world since about 1880, so we only have about 140 years of weather data, which to an average person sounds like a lot, but the weather and the climate are much, much older than that."

Another problem is that's around the time humans began burning coal and oil.

"We've been measuring weather during the period in which humans have been modifying the climate, so by going back 2,000 years we have a record of temperature before humans had such a profound impact on our climate."

But thanks to the new database, scientists can now have a better understanding of what earth's climate was doing naturally well before people were burning fossil fuels.

"The more data, the better because the more solid are your conclusions," he explained.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)