Scientists in race to test CRISPR gene-editing technique on cancer

First human trials are pending

A novel gene-editing technique with potential to revolutionize cancer treatment has scientists in a race to test it on humans.

As the scientific journal Nature announced last week: "Chinese scientists to pioneer first human CRISPR trial."

But wait. On the same page, there's a link to another story from a month ago: "First CRISPR clinical trial gets green light from U.S. panel."

So who will be first in the race to use CRISPR in humans the U.S. or China? And what are they using CRISPR to do?

If you haven't heard about CRISPR yet then all of this might seem underwhelming. But for scientists likeJasonMoffat, at the University of Toronto, it's amazing news.

"That's fast," he said. "They're pushing the technology really hard."

That's fast. They're pushing the technology really hard.- Jason Moffat, University of Toronto

CRISPR is a revolutionarygenetic editing technique that has been rocking the world of biologyever since researchers first realized they could use it to edit the genome of any species with ease and precision never possible before.

At U of T,Moffatis usingCRISPRto identify the set ofgenes that are essential for cell survival.

"It gives you the tools to ask questionsabout whatthings are doing that wecouldnever do before," he said. "It's really exciting."

Scientists are now usingCRISPRin a range of wild experiments. They've already designed a mechanism that could wipe out mosquitoes. And they're also toying with using itto bringthe woolly mammoth back to life.

It's a tool so powerful, it could be used to permanently alter the human genome in a way that could be passed on to future generations.

Earlier this year, scientists from around the world gathered for an unprecedented summit in Washington, D.C., and agreed to avoid using CRISPR forhuman genetic engineering

CRISPR against cancer

But what can CRISPR do in research oncancer? That's the question that will be asked in these human trials.

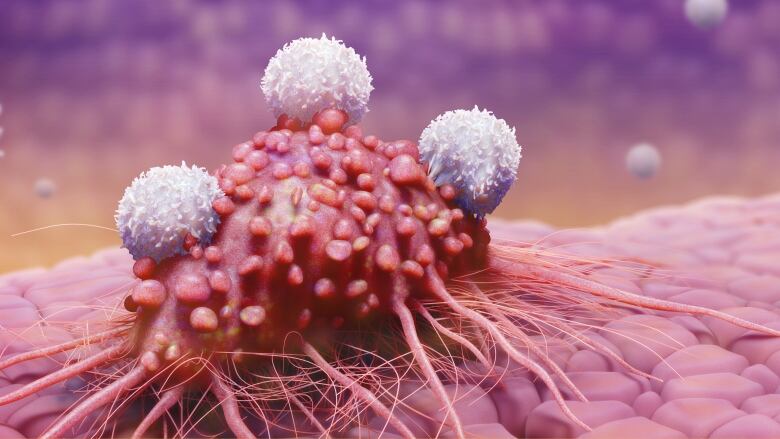

CRISPR isnot a therapy on its own. It's a tool. But because of its precision, researchers arehoping it will be able to make genetic edits that are more effectivethan thetraditional gene-editing techniques,to trigger a patient's immune system to kill cancer cells.

They will harvest a type of immune cell, known as T cells, from a patient's blood and thenuse CRISPR to tinker with a particulargenein a way thatwill activate theT cellsto attack cancer cells. And then they will put the CRISPR-edcells back into the patient's body to destroy tumours.

"Thesefirsttests,if done properly,are going to pave the way for how to useCRISPRto treat disease," saidMoffat.

What risks getting lost in the excitement over these first CRISPR trials is the sobering fact that it might not work. There is the ever-presentrisk of unintended consequences, including CRISPR's tendency to make unpredictable genetic edits in unwanted places.

And experiments to genetically alter cells and reprogramthe immune systemare inherentlyrisky. There's a danger of triggering a catastrophicimmune response known as acytokinestormthat can fatally overwhelm the body. And by unleashing Tcellsagainst cancer,it's also possiblethey'll start attacking normal tissue, too.

Gene therapy tragedy

And last month, a clinical trial testing the same T cellapproach, but without using CRISPR,was shut down by the FDA after several patientsdied. The trial has since been allowed to resume.

The Chinese scientists have secured all thenecessaryapprovals and are scheduled tobegin their trial usingCRISPR-edited cells in 10lung cancer patientsnext month. The U.S. team still needs FDA approval, and they expect to start their trial on 18 patients later this year.

Another caveat: These arePhase 1 trials only. That means the scientists are studying toxicity and side-effects and basic biological responses. Even if all goes well, the trialsto see if the approach actuallyworks against cancerare still many years away.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)