How and why people 'microdose' tiny hits of psychedelic drugs

We are still a far cry from saying this is medicine, researcher says

Illegal, underground and said to be brimming with health benefits the practice of microdosingpsychedelicdrugs is growing increasingly popular, yet it remains relatively unstudied and its reported benefits unproven.

A group of Canadian researchers is hoping to change that with new data that begins to shedlight on how and why people microdose, and what they say are its effects and drawbacks.

Microdosing is the practice of taking minute doses of hallucinogens like LSD or psilocybin(the active compound in so-called magic mushrooms)for therapeutic purposes. The amounts are too small to produce a high but large enough to quell anxiety or improve mood, according to users.

Researchers at the University of Toronto andYork Universitycollaborated on the study, which they say is the first of its kind.

Reports of improved mood, increased focus

The team targeted microdosing communities on Reddit and other social media channels with an anonymous online survey last year. They received 909 completed responsesfrom current and formermicrodosers as well as others who had no experience with the practice.

The survey yielded information about how much and how often people microdosed: typically 10 to 20 micrograms of LSD (about one- or two-tenths of a tab)or 0.2to 0.5 grams of dried magic mushrooms, about once every three days or once per week.

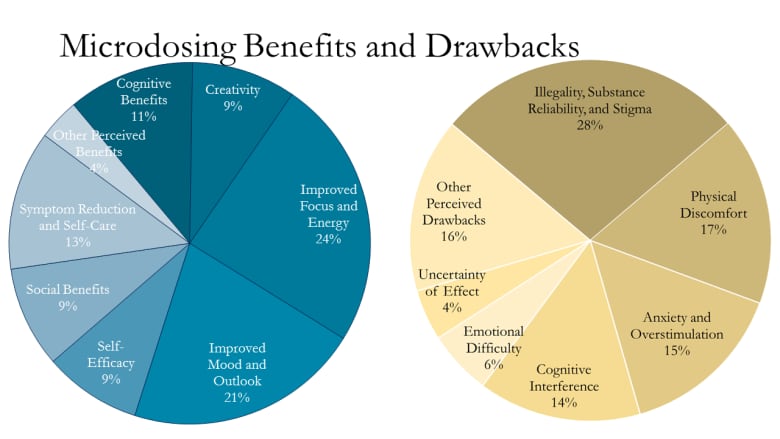

Those who microdosedreported a number of benefits, including improved mood, increased focus and productivity, and better connection with others.

The team also conducted a series of tests to compare users with non-users.

For example, to gauge creativity,participants were asked to find as many uses as they couldfor everyday objects. Researchers tested for wisdom by askingsurvey participantshow much they related to a series of statements like"At this point in my life, I find it easy to laugh at my mistakes."

They found that microdosers scored higher on both creativity and wisdom, andlower on negative emotionality and dysfunctional attitude tied to depression and anxiety.

Study co-author Thomas Anderson, a PhD candidate and cognitive neuroscientist with the Regulatory and Affective Dynamics Lab at U of T, called the results "really promising."

'A far cry' from calling it medicine

But both lead authors caution against drawing a causal connection.

"Our results certainly justify further research, but it's important to take them with a grain of salt," said co-author Rotem Petranker,a graduate student in social psychology at York.

"What this truly means is that we need to study it further in a lab setting so we really get an idea of how much of these reports truly are caused by the substance."

Anderson also notedthat a small group of microdosing respondents listed effects contradictory to the reports of others, such as decreased focus and increased anxiety.Some also reportedphysiological discomforts, such as feeling too hot or too cold.

The most common complaint from respondents, however,was about the difficulties of the practice given its illegality and related stigma. Having to obtain the substances underground also makes it hard to ensure a safe, reliable supply and consistent dosage.

The researchers made clear theydo notendorse microdosing as a treatment.

"We are still a far cry from saying this is medicine and we should prescribe it to people. I think we should do a lot more research before we can say that," Petranker said.

Barriers to research 'formidable'

Canada was once a world leader in the exploration ofpsychedelic drugs for medicinal use, according to Kenneth Tupper,adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia and a director at the B.C. Centre on Substance Use.

Saskatchewan's Weyburn Mental Hospitalwasconsidered a hub for cutting-edge research in the field in the1950s, when psychiatrists Abram Hoffer and Humphry Osmond experimented with administering LSDto volunteers, co-workers, friends, family members and themselves. They eventually used the drug to treat patients with alcohol addiction, often successfully, and their work was recognized internationally.

However, the work there and elsewhere was deraileddue to concerns overrecreational use and the social climateof the time, Tuppersaid.

"The throwing-the-baby-out-with-the-bath-water reaction happened [because of]the non-medical use on the street. That really did put us back many decades in terms of potential promising clinical utility."

That's changing, he said, but there is still a wayto go.

"More and better research is only going to happen with a shift in regulatory authorities' and medical communities' willingness to look at these things, which is starting to happen but, really, the research funding [is not available]."

The illicit nature of the substancesalso poses a legal hurdleto research, according toMark Haden,public health researcher at UBC andexecutive director of Canada's Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

"If you actually want to start giving psychedelics to people [for research], the barriers are formidable," he said, adding that reclassifying psychedelic drugs would help clear the path.

In Canada, hallucinogens such as LSD andpsilocybin, are classified as Schedule III controlled substances, which means possession requires a licence/prescription, or carries a maximum penalty of three years in prison.While Canadians will soon be able to purchasecannabis legally, the federal governmentearlier this week confirmedit has no plans to decriminalize other drugs.

Hope for first lab-based microdosing trial

Hadensayscontinued researchis importantgiven the host of illnesses and disorders that we do not yet have effective treatments for.

"For instance, depression," he said. "Maybe what will come out of this is that some people will be helped with really large doses used in therapeutic contexts and other people will behelped more by tiny amounts of psychedelics as they go about their day."

Despite the challenges, Canadians are conducting more research in this area: clinical trials are being conducted on the potential therapeutic benefits ofMDMA-assistedpsychotherapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder, and on psilocybin-assistedtreatment of substance use disorders.

Anderson andPetranker'steam will be publishing the findings from their survey in three upcoming research papers.

They also hope to conductlab-based trials where psychedelics can be administered in controlled environments.

"No one has done randomized, placebo-controlled trials for microdosing," Anderson said.

"We are hoping to be the first."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)