Conservatives at historic lows in the polls, but still competitive

Shifting voter base and divided opposition keep Conservatives in the running

The Conservatives are heading toward their lowest share of the vote in any election since the Second World War.

But that may not be as bad as it sounds for Stephen Harper's party. With a voter base that has shifted to their advantage and divided opponents, few are prepared to write off the Conservatives' chances in October's federal election.

Averaging 28.4 per cent in the polls, the Conservatives are currently on pace for their worst showing as a united partysince 1945, when John Bracken's Progressive Conservatives captured just 27.6 per cent of the vote.

If election results matched the polls today, the Conservatives would have their worst results in British Columbia and Alberta since the 1960s.

We have to go back to 1867 to find an election where the Conservatives' predecessor parties did more poorly than their current polling numbers in Atlantic Canada, and that was whenthe Anti-Confederates were the favourite option in Nova Scotia andbefore Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador had even joined the country.

However, we only have to go back as far as 2004 to find worse results for the Conservatives in Ontario and Quebec. And that is an indication of how the Conservative base has shifted some of its weight from Western to Central Canada.

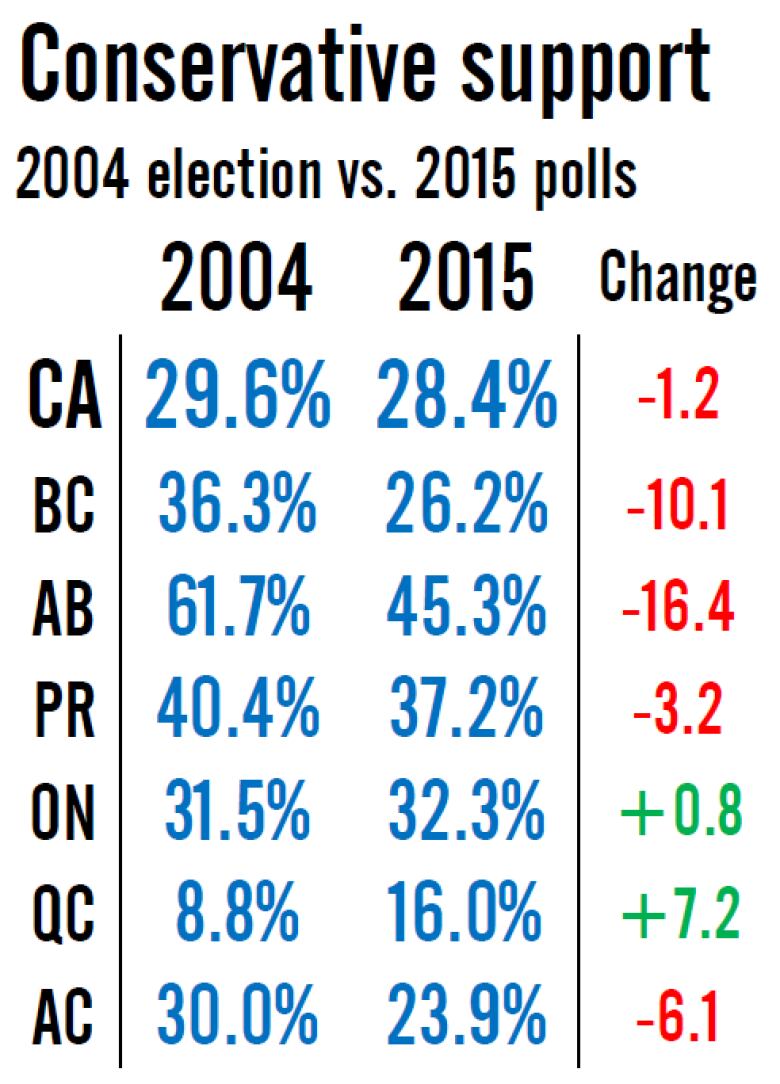

Conservative base, 2004 vs. 2015

The 2004 election is a good example of what happens when the Conservatives are reduced to their base. In that election, the first as a merged party under Stephen Harper, the Tories took 29.6 per cent of the vote and formed the Official Opposition. That is little different from where the party stands today. It is also a good proxy for a Conservative "floor," as the party and its predecessors have historically captured somewhere between 29 and 32 per cent at their lowest ebbs.

But the Conservative party in 2004 was still heavily rooted in its Reform Party base in the West. The Conservative party of today, again reduced to its base of support, is far more evenly balanced.

As the chart shows, the Conservatives have seen their support plummet in the western parts of the country. The Conservatives are currently polling 10 points below their performance in British Columbia in 2004, and 16 points below their tally in Alberta. In the Prairies, the Tories have fallen less dramatically.

The Conservatives have also dropped significantly in Atlantic Canada, falling to just 24 per cent today from 30 per cent in 2004.

But a rise in Ontario and Quebec has compensated for these losses. Despite being about one point below its national standing in 2004, the Conservatives are up about a point over their performance that year in Ontario. The biggest change has come in Quebec, where the Conservatives are polling at nearly double their 2004 support. The party has gone some way to re-connect with the old PC base it once held in the province.

A more efficient floor

This shift from Western to Central Canada gives the Conservative Party far greater vote efficiency. Their losses in Alberta, for instance, do not translate into a reduced seat count, whereas their gains in Quebec and Ontario pay outsized dividends.

Despite shedding more than a quarter of their supporters in Alberta, the Conservatives still hold such a wide lead they should be able to match the 26 seats the party captured in the province in 2004. However, this represents a lower share of seats, as the total in Alberta has increased from 28 to 34 since then.

But the drop of support in British Columbia has been steep, and could cost the party dearly. The Conservatives won 22 seats in B.C. in 2004, but gains by the NDP could see Conservatives take just eight seats there today (and this despite the increase in the number of seats in B.C. to 42 from 36). A modest drop in support coupled with new riding boundaries in Saskatchewan also means a potential big drop in seats for the Conservatives in the Prairies.

In Atlantic Canada, a more divided opposition (the Liberals have 41 per cent today compared to 44 per cent in 2004, and the NDP 28 per cent compared to 23 per cent in 2004) means the Conservatives could match the seven seats won in the region in 2004.

In all, compared to 2004, the Conservatives stand to lose about 20 seats in the West. These are more than made up for by the 36 seats or so the party stands to gain in Ontario and Quebec.

The Conservatives' gains in Quebec cannot be only chalked up to greater efficiency doubling their support has some consequences. But their task is aided by a more divided opposition. In 2004, the Bloc Qubcoiswon 49 per cent of the vote in Quebec and the Liberals 34 per cent. Today, the Liberals, NDP and Bloc together do not combine for as much support as those two parties had 11 years ago.

The most important difference, though, is in Ontario. In 2004, with 31.5 per cent support, the Conservatives won just 24 seats. Today, with 32.3 per cent, the Conservatives could win 52 seats.

The 15 new seats in Conservative-friendly areas helps matters, but more important is the divisionto the left of the Conservatives. The split is dramatic, with the Liberals holding 31 per cent support and the NDP holding 30 per cent in the polls. By comparison, the 2004 Liberals had 45 per cent support in Ontario and the NDP just 18 per cent. As long as neither opposition party convinces enough voters to flock to them, the Conservatives can win a lot of seats that would have been out of their grasp with a similar level of support in 2004.

The net effect of theshift of the Conservative baseis about 15 or 20 seats in the party'sfavour. In a three-way contest, that is more than enough to propel the Conservatives from third to first place in the seat count, depending on how the NDP and Liberals divvy up the remainder.

Looking at the polls alone, these look like the worst of times for Stephen Harper and the Conservatives. Nevertheless, they are still in the running for re-election in October.

ThreeHundredEight.com's vote and seat projection modelaggregates all publicly released polls, weighing them by sample size, dateand the polling firm's accuracy record. Upper and lower ranges are based on how polls have performed in other recent elections. The seat projection model makes individual projections for all ridings in the country, based on regional shifts in support since the 2011 election and taking into account other factors such as incumbency. The projections are subject to the margins of error of the opinion polls included in the model, as well as the unpredictable nature of politics at the riding level. The polls included in the model vary in size, dateand method, and have not been individually verified by the CBC.You can read the full methodology here.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)