The Rebel and the NDP, why not to provoke Ezra Levant

Thanks Rachel Notley, for helping define what journalists are, or maybe aren't?

Journalists entertain all sorts of self-aggrandizing notions about what we do.

The big one is that we are a profession, which we pretty clearly are not. We don't even really qualify as a trade.

Professions generally have minimum qualifications. You need a degree in accounting to be an accountant, for example.

And a tradesman, like a mechanic, or a furnace installer, requires a licence something to prove you can actually do the job.

Not a journalist. Journalists don't even have to finish high school.

- Notley's NDP lifts ban on The Rebel, says it made mistake

- Justin Trudeau boycotts Sun Media over Ezra Levant rant

Professions also tend to regulate themselves.

If lawyers or doctors or pharmacists breach the clear ethical rules governing them, they can be formally charged and punished by their peers.

The car mechanic or furnace installer can lose his licence.

But regulating journalism? Out of the question, for the sake of democracy itself, my peers would argue.

There are no national journalistic standards, and no way to enforce them if they existed.

Journalists can root through people's garbage, mislead interview subjects to gain their confidence, appoint themselves arbiters of people's privacy, and decide whose story is worth public consideration, and whose isn't the only people we answer to are our bosses.

Most of us do try to tell the truth, but let's be clear: there isn't any law or regulation that says we even have to do that. Some big organizations have codes of conduct, others don't. Such rules as do exist are often interpretable.

And anyway, what is the truth? There are many truths.

No basic qualifications

Our only legal leash is libel law, and we hire lawyers to deal with that.

Massive blunders can be shrugged off.

The day after the National Post printed a huge front page scoop in 2006, reporting that the Iranian parliament had voted to force Iranian Jews to wear identification badges, a member of the Asper family, which owned the paper at the time, conceded the story was complete malarkey.

But, he added, it "wasn't a stretch." You know, it could have happened. The editor-in-chief was still the editor-in-chief the next day.

Journalists also resist any effort to formally define the job. In 1988, the federal government wanted to include journalism on the list of occupations that would enjoy relatively free cross-border movement under the first Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement.

But that meant setting down in law a set of basic qualifications like a journalism degreeand journalistic organizations put up such a fuss that the idea was dropped.

The upshot: basically, anybody who says he or she is a journalist is a journalist.

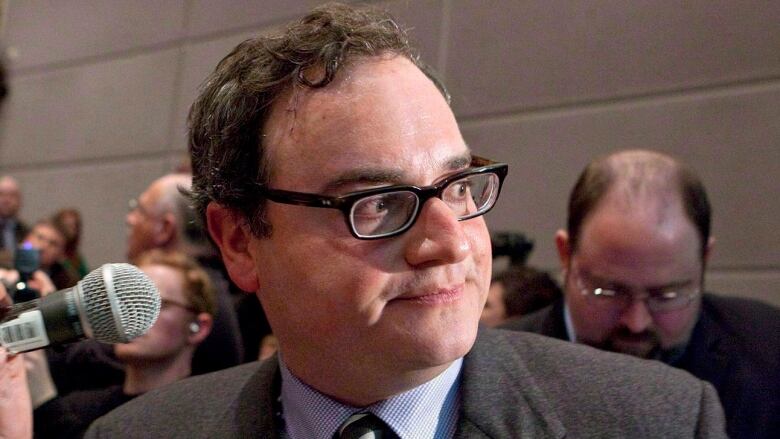

Which brings us to Ezra Levant.

Career launched

After Sun News Network was shuttered a year ago, Levant was suddenly a big mouth with no bullhorn.

He'd built a long career as a right-wing stunt man; I had the dubious honour of "discovering" him back in 1993, when he was a University of Alberta law student in Edmonton agitating against the school's attempts to set aside places for aboriginal students.

Levant posted signs announcing the university had adopted an anti-Semitic policy, and called what amounted to a news conference.

He then told those in attendance that since Jews aren't aboriginals, U of A was discriminating against Jews.

The dean of students, foolishly taking the bait, threatened Levant with expulsion for hate speech. He went public, and his career was launched. First as a political operative, then in conservative media.

Levant works from the same playbook used by Sean Hannity and Rush Limbaugh and the other big names in right-wing American talk radio. Red-meat righties love him.

Knowing how prissy and self-righteous some progressives can be, one of Levant's standard plays is to goad some group or figure on the left, then portray himself as one brave man standing up to those who would take away our freedoms. He provoked Justin Trudeau by taking ugly personal shots at Trudeau's father and mother.

This week, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley and her NDP government became the latest to take the bait.

A mistake

Notley's staff, outraged at Levant, summarily decided to ban the correspondent from The Rebel website from government news conferences.

Their argument: Levant himself once denied being a journalist, so the Rebel is not a journalistic outlet. (In fact, Levant, testifying once in a libel trial, said he is a pundit and commentator, not a reporter.)

Now, it's true that The Rebel's Alberta bureau chief, Sheila Gunn Reid, doesn't fit the conventional notion of a journalist.

On The Rebel site, she describes herself as a "stay at home mom of three and a conservative activist with strong ties to the oil patch."

But then again, Toronto journalist Linda McQuaig works from home a lot, too, is a mom of one and an NDP activist she actually ran for the party as a candidate in the last general election.

Levant would argue that the mainstream media tendto regard left-leaning activist/journalists with admiration, and right-wing activist/journalists with some distaste. And he'd have a point.

Anyway, Levant used Notley's decision to blast his own trumpet and was, suddenly, back where he so loves to be: in the middle of a controversy, or as he modestly put it on his website, "an international firestorm."

Canadian journalists and publications, rolling their eyes, did what he knew they would do: they lined up to denounce the Notley decision, or as Levant loves to put it, "stand with Ezra."

Notley was told in pretty clear terms that defining journalists and excluding the ones you don't like are unacceptable.

Fairly quickly, she backed down. Banning Levant was "a mistake," her office said in a statement. A retired veteran wire service reporter was asked to review the whole matter and report back.

All to the good. Levant is a journalist if he says he's one, and he does.

Mind you, it would have been wonderful to hear him raise his fearless voice in defiant criticism when Stephen Harper's underlings were gagging public servants, shutting down access for journalists, controlling questioning at news conferences and generally making Notley's crew seem like amateurs.

But then, there's nothing that says a journalist has to be consistent, either.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)