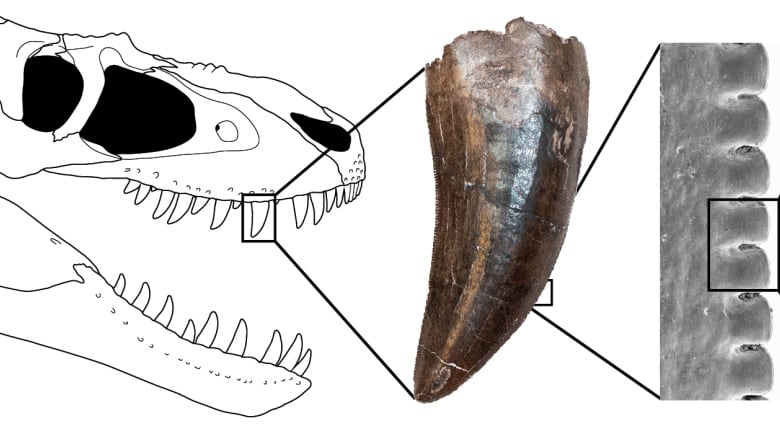

Tyrannosaur teeth were serrated like steak knives

U of T study shows tyrannosaur teeth had deep serrations that made teeth resistant to breaking

If you want to know the secret behind the success of Tyrannosaurus rex and its meat-eating dinosaur cousins, look no further than their teeth.

Scientists on Tuesday unveiled a comprehensive analysis of the teeth of the group of carnivorous dinosaurs called theropods, detailing a unique serrated structure that let them chomp efficiently through the flesh and bones of large prey.

Theropods included the largest land predators in Earth's history. They first appeared about 200 million years ago and were the dominant terrestrial meat-eaters until the age of dinosaurs ended about 65 million years ago.

The study involving eight theropod species revealed their previously unknown tooth complexity. Internal dental tissues were arranged in a way that reinforced the strength and prolonged the life of teeth that were serrated like steak knives for easy dismembering of other dinosaurs.

Bone crushing

University of Toronto Mississauga paleontologist Kirstin Brink said fossil evidence showed that T. rex's teeth could crush bone. Its teeth have been found embedded in the bones of its prey and chunks of bone appear in its fossilized dung.

"But the serrations were most efficient for piercing flesh and gripping it while ripping off a chunk of meat, called the 'puncture and pull' feeding style," Brink said.

The researchers analyzed slices from fossil teeth using a powerful microscope and a sophisticated device that revealed tooth chemical properties.

They studied teeth from: the early and relatively small Coelophysis; bird-like Troodon; large predators Allosaurus, Gorgosaurus, Daspletosaurus, Tyrannosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus; and big, semi-aquatic Spinosaurus.

- Tyrannosaurs prowled in packs, B.C. tracks show

- Daspletosaurustyrannosaurs fought, ate each other

- Spinosaurus is the first semi-aquatic dinosaur ever discovered

The teeth of Tyrannosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus measured up to 23 cm (9 inches) long.

"In theropods, the serrations are larger and deeper than the superficial view suggests, making them stronger and longer lasting, less likely to get damaged or worn," University of Toronto Mississauga paleontology professor Robert Reisz said.

Dinosaurs were able to continuously grow teeth throughout their lives. When a tooth was broken, another could replace it.

"It could take up to two years for a tooth to grow back in the big theropods like T. rex. Therefore, having specially reinforced teeth means less tooth breakage and less gaps in the jaw, leading to more efficient eating," Brink said.

The Komodo dragon, a lizard up to 3 metres(10feet) long from Indonesia, is the only living reptile with serrated teeth closely resembling those of theropods although these teeth evolved independently of those of the dinosaurs, Brink said.

The research appears in the journal Scientific Reports.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)