Gene doping risky for athletes

Athletes and coachesmight be tempted to try usingthe already readily available tools of gene therapy to boost performance, but thepractice isn't ready to be tested on humans, researchers warn.

The experimental field of gene therapy involves injecting the body with new genes that produce therapeutic proteins meant to block disease.

Theodore Friedmann, chair of the World Anti-Doping Agency's expert group on gene doping, fears that cheaters in sports will turn to gene therapy in their effort to be faster andstronger.

He and his colleagueswrote a policy paper on the subjectthat will appear in Friday's issue of the journal Science.

"Some athletes and coaches will be tempted, prematurely and unwisely, to take advantage of results packaged by some as performance-enhancement 'breakthroughs,' even if they are untested in humans and the only 'breakthrough' is faster or stronger mice," the researchers wrote.

The article says gene therapy has complicated international competitions like the Olympics.

Online marketing campaigns target athletes with ads focusing on how treatments can "alter muscle genes activating your genetic machinery."

Deadlyrisks

Already, scientists doing experiments in lab animals have been approached by athletes volunteering themselves as human test subjects.The athletes want to be like the "Schwarzenegger mice" that havean extra copy of a gene that led the critters tobecome 30 per cent stronger.

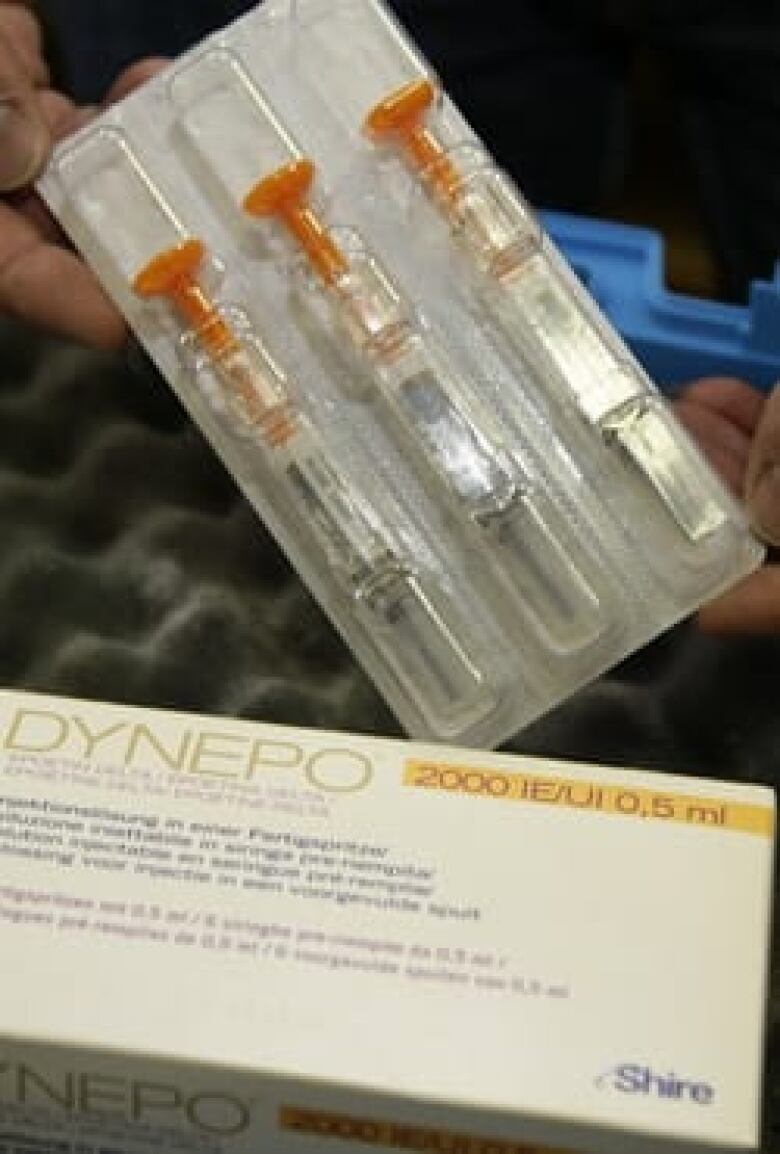

In 2006, German track coach Thomas Springstein was found trying to obtain Repoxygen, which theoretically boosts the body'sproduction of oerythropoietin, or EPO, a hormone that drives production of oxygen-carrying red blood cells.

When a product similar toRepoxygen was injected into baboons, the animals' circulatory system became so clogged with extra red blood cells that theexcess blood had to be drained to save their lives.In anotherexperiment, healthy primates had anunexpected immune reaction to the virus used to deliver theEPO gene. Theanimalswere no longer able to produce red blood cells and had to beeuthanized.

The 1999 death of 18-year-oldJesse Gelsingerin Arizona was linked with a gene therapy study for a metabolic disease, and children havedevelopedleukemia after gene therapy treatment for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) or "bubble boy disease."

Despite the risks,the interest in applying gene-based manipulations to athletes has been growing. The Science article pointsto an Associated Press report that described an incidentprior tothe 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing in which a Chinese doctor offered to sell stem-cell therapy to a German reporter posing as a swimming coach.

Race against cheaters

"We don't know the technology in fine enough detail to predict or to avoid problems," Friedmann said.

"It's not enormously complicated to do it badly."

"The problem with sport, of course, is that there's so much money and so much pressure to develop novel approaches to winning that they can dangle a lot of money in front of people.

The authors of the article say it is not clear whether any athletes have used gene doping, but it is inevitable that they will.

In the race between regulators and cheats, WADA has had gene doping on its list of prohibited substances and methods since 2004, trying to keep a step ahead by developing ways to detect gene doping as animal experiments continue.

"The scourge of doping in our sport is disheartening to athletes, and certainly, it's a challenge for science to keep ahead of the dopers," said Chandra Crawford, a gold medallist in women's cross country 1.1kmsprint at the 2006Torino Games. "I know it's a tough struggle, but we have to do everything in our power to get it cleaned up."

Starting Thursday, Olympic organizers plan to administer 2,000 blood and urine tests in Vancouver in the weeks ahead,the most rigorous anti-doping effort in the history of the Olympics.

The agency is funding international research teams that are working to detect potential gene doping, based on its effects on protein levels, for example. The tests don't detect all gene doping yet andaren't conclusive, but they mayshow if an athlete's muscle mass or performance suddenly improved andraise a red flag that mightspur further investigation.

With files from The Associated Press

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)