The hunt for Radovan Karadzic and Serbia's real destiny

Currently the host of CBC Radio's As It Happens,Carol Off spent many years covering the events in the Balkans and the war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. In 1998, she traveled to the region for CBC TV's The National, which resulted in the documentaryLooking for Dr. Karadzic.

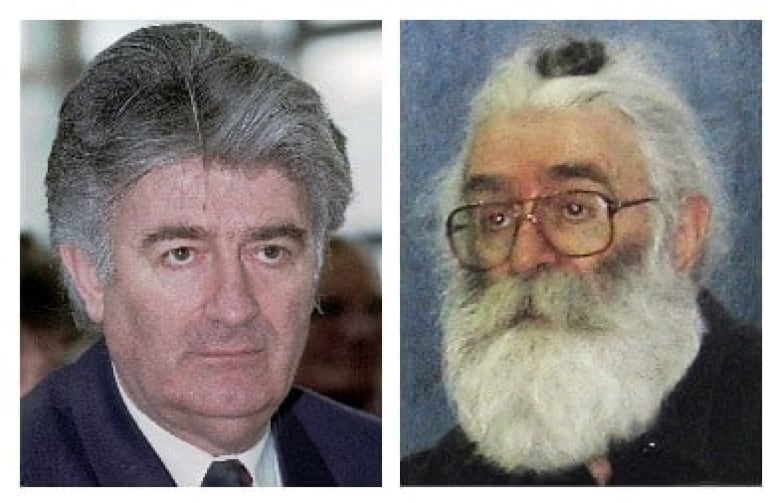

There were no rumours this time. Or at least none that anyone bothered to pass on. Those of us who have followed the saga of Radovan Karadzic man on the lam for nearly 13 years have heard countless times that he was about to be arrested.

We would alert our newsrooms, book flights, prepare for the big trial, only to learn that the wily silver-haired psychiatrist cum ethnic nationalist had evaded capture once again.

Sometimes even police had arrived just moments too late: the cigarette still smouldered in the ashtray; the coffee satstill warm in the cup; the back door swung in the breeze as Karadzic made yet another brilliant escape, leaving authorities baffled.

The 'exclusive' interview

The other bad tip that Karadzic watchers often fell for was the offer of an inside interview with the man himself. One of his supporters had offered to set up such an encounter for me in the fall of 1998 and so I headed overseas.

Of course, my "exclusive" fell through but my backup plan was to travel the former Yugoslavia and visit all of the places where Karadzic had been sighted since his indictment in 1995 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague.

CBC reporter Nancy Durham joined me for the excursion. We drove through the Balkans for weeks, interviewing those who claimed to have harboured Karadzic (or would have risked their lives to do so if they had the opportunity), and prepared the CBC documentary, Looking for Dr. Karadzic.

The most intriguing character we met was Radovan's mother, a tiny, wrinkled old woman, living in a large house in Montenegro, undoubtedly provided from her son's considerable black-market enterprises.

She claimed she hadn't seen him in months, though it was well-known that he visited often.

She refused to grant us a formal interview. But as she talked freely about Radovan and about a prophesy made at his birth that he was destined for greatness, Nancy pulled out the camera, while our translator, Belgrade reporter Katrina Subasic, peppered her with questions.

Black magic

When she finished talking, Karadzic's mom accused us of having employed black magic in order to trick her in to talking on camera.

We learned later that Karadzic's people had instructed her not to talk to reporters.

But on that day, she produced a giant bottle of Black Label whiskey and poured us drinks while Radovan's niece told us that someday, her uncle would be hailed as an international hero for his efforts to protect Christian Europe from the Muslim hordes. The Karadzic family, like all those we met, did not deny that the Bosnian-Serb leader had been involved in a campaign to push Muslims and Croats from Bosnia. But they insisted it was all an act of self-defence.

The "Turks," as they often called Bosnians, were plotting to eliminate all the Serbs, they said, and it was a matter of kill or be killed.

They also saidthe Croats werefascists with the same designs.

Croatia was an ally of Germany in the Second World War and the Muslims do descend from Turkish ancestry. But Yugoslavia had been an effort to unite the Balkan Slavs into a single nation, and these different groups had co-existed for decades until the war in the 1990s brought it all to an end.

Greater Serbia

Karadzic had declared that Serbs could not live securely with other Balkan peoples. They needed their own ethnically pure state and that meant non-Serbs had to move someplace else.

And so the siege of Sarajevo, the mass-killing of Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica and the removal of as many as two million people from Bosnia parts of which form the indictment against Radovan Karadzic were seen as part of the war effort.

As far as his supporters were concerned, Karadzic was trying to protect them. The rest of the world simply didn't understand their tragic history of persecution and their need for what was called Greater Serbia.

Searching for Dr. K

By the time I went looking for Karadzic in 1998, Bosnia was divided, Serbian ambition was thwarted and all that was left to fight for was the freedom of Radovan.As we toured the many places where the flamboyant doctor might be hiding, we met his adoring fans. They were blind to the mafia-like operations that supported Karadzic the black-market petrol and cigarettes, the money laundering and gun running and which helped to impoverish and criminalize their society.

One Karadzic groupie took us home to show us his shrines to Radovan photos and posters with votive candles lit in tribute. They coexisted on his walls with icons of Serbia's patron saint.

The man also told us that he was hiding his hero in his heart. His wife kissed a picture of Karadzic on the lips.

Ethnic purity

The irony here was that Radovan Karadzic is from neither Bosnia nor Serbia; he hails from the remote Montenegrin village of Petnica, where ethnic purity is reduced to its essence.

We visited the wary little mountain community one afternoon and found it wasn't difficult to find Radovan's family. In fact, everyone in the village was named Karadzic.

Radovan's relations told us that some outsiders had once attempted to buy land and to build a house there. But local people had burned it down.

In the cemetery, every tombstone bore the name Karadzic and all the men we met sported the same silvery mane of hair for which the Bosnian-Serb leader is famous.

Despite Radovan's university degrees, his published poetry and his command of rhetoric, the doctor's birthplace best sums up his paranoid worldview that one is safe only with one's own.

That is what makes his arrest by Serbian authorities so spectacular. President Boris Tadic has taken the enormous political (and perhaps mortal) risk of believing that most Serbs want to join a much larger entity the European Union instead of turning inward as the xenophobic doctor wanted them to.

The Karadzic arrest represents more than just a fulfillment of an obligation.It's an act of trust that cannot be betrayed.For Karadzic watchers like myself, there will now be a trial where the facts of the case must be built meticulously if there is to be a conviction.

There is a chance here to learn a great deal about how the war began and who started it. A fair and just trial might prove rewarding to all the victims of the Bosnian conflict, no matter what their ethnicity.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)