DAY 1: En route to Beirut

Nov. 1, 2010 The first time I entered the Shatila Palestinian refugee camp was only days after I had moved to Beirut to report for CBC. It was Sept. 17, 2004, the 22nd anniversary of the 1982 massacre that claimed the lives of hundreds, possibly thousands, of Palestinians during the Lebanese civil war and catapulted Shatila, and the neighbouring Sabra camp, into headlines and infamy.

Until then, I had only read about Shatila and its woes in books and newspapers. I had imagined it bigger, more sprawling and more melancholy. But it was small and noisy, thick with people, far more bustling than the picture in my head. For some reason, I hadn't expected to see so many children.

It seemed everyone there had become accustomed to the sudden flurry of activity each time Sept. 17 came along the sudden interest of journalists, the influx of foreigners who'd come to listen to speeches and pay their respects to the dead. Residents including children obligingly recounted the horrific days when bodies were strewn all over the streets, how they, or a relative, had somehow miraculously survived it all.

I would return to Shatila many times after that day on various other assignments, and to several other refugee camps still in existence in Lebanon, where Palestinians enjoy few rights. And while over the years, the rest of Beirut and Lebanon were slowly sheddingtheir civil war wounds and renewing themselves, the camps barely changed.

Nahlah Ayed's Shatila blog

- Day 1: En route to Beirut

- Day 2: Small signs of progress

- Day 3: Sharing details, but with dignity

- Day 4: Artifacts of exile

- Day 5: Shatila's space problem

- Day 6: Camp politics

- Day 7: A litany of woes

- Day 8: Talking about Arafat

- Day 9: Dreaming big in Shatila

- Day 10: Living with the trauma of camp life

- Day 11: Celebrating sacrifice in Shatila

- Day 12: Stuck in Shatila

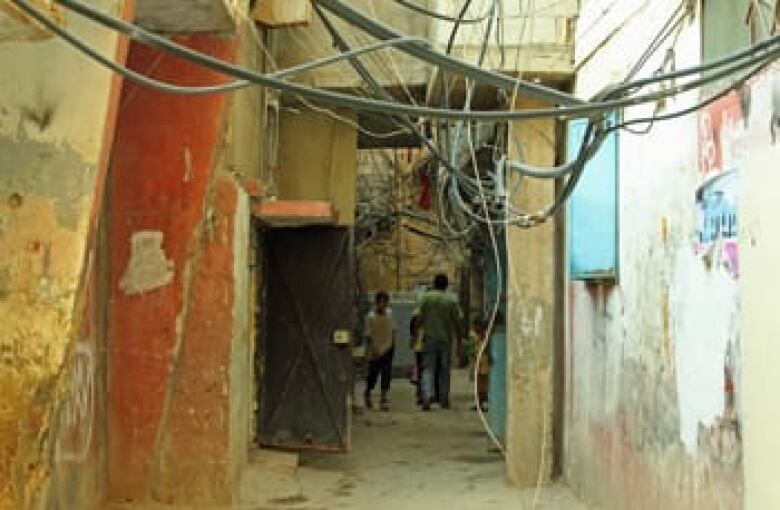

Because it had set, predetermined borders, Shatila never really grew except vertically, as residents added floors on top of haphazardly built concrete homes to accommodate married children. Open sewers and bunches of electrical wiring guided visitors through its narrow alleys. The people were exceptionally poor, and if there was any change over time, it was only a further downturn in their fortunes.

The children were always there, along with the constant reminders of loss and mourning: in class, at home, in the graffiti on the walls. You couldn't have a conversation with anyone there without it eventually turning to the massacre, or to the circumstances under which that person's family fled Palestine and ended up in Lebanon. Children and grandchildren of the original refugees recited the story as if they had lived through it themselves.

On top of all that, violence was always a constant. Before and after the massacre, Lebanon regularly erupted in fighting and brutality.

With no passports and no means, Shatila's residents could never really flee danger no matter how threatening.

Just during my five years in Lebanon, they lived through Lebanese sectarian clashes, a string of car bombings and destabilizing, massive political protests. While many Lebanese left, peoplein the camp stayed on even during the 2006 conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, whose power base is a short distance away from Shatila and had invited some of the heaviest aerial bombing of the conflict.

What is it like for new generations of children in Shatila who have again grown up in poverty, constantly surrounded by the stories of the violence that came before? That is just one of the questions we hope to answer when we visit the camp to film ouronline documentary.

It has been well over a year since I was last in Shatila, but I suspect we will find that little has changed.

[IMAGEGALLERY galleryid=131 size=large]

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)