How monitoring wastewater provides the most accurate look at COVID-19 infection in Calgary

It detects asymptomatic cases and removes sampling bias, says infectious disease specialist

As the Alberta government scales back on widespread PCR testing to focus on those in high-priority settings such as health care, the province is now relying on wastewater surveillance more than ever before to track the prevalence of COVID-19 in Alberta.

"Omicron is spreading farther and faster than anything we've ever seen before, and no one in Canada will be able to maintain PCR testing for every community case with mild symptoms," said Dr. Deena Hinshaw in a COVID-19 update on Dec. 23.

WATCH | How researchers keep track of COVID levels through wastewater testing

The province's wastewater and the amount of infection in it has been monitored for two years by a group of 23 researchers in a joint project with the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta.

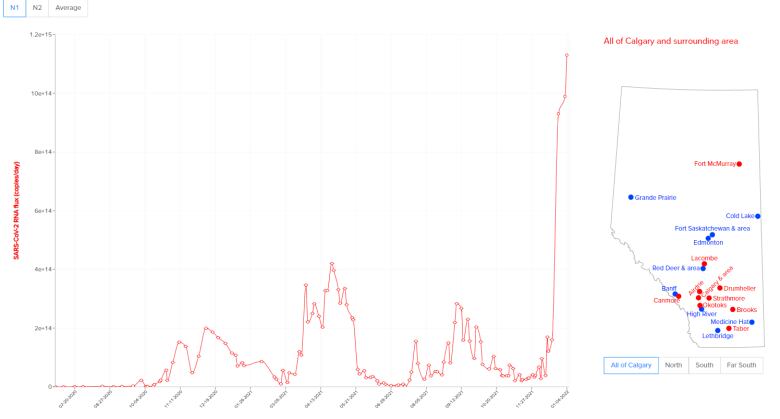

The data, which is updated publicly three times a week, depicts the amount of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the province's wastewater. That's the virus that causes COVID-19, which individuals shed in their feces before symptoms arise.

That's according to Dr. Michael Parkins, one of the research leads on the wastewater monitoring project in Calgary. He's also an associate professor at the University of Calgary's Cumming School of Medicine and section chief of infectious diseases for Alberta Health Services.

He says the major advantage to wastewater testing is it's inclusive and comprehensive.

"It captures all members of the society, even those that are marginalized and don't have the opportunity to get tested. It tests all people, whether they're symptomatic or not."

Dr. Jon Meddings, dean of the Cumming School of Medicine, says they're lucky with this particular virus. Not all viruses are shed into the gut, making themdetectable in sewage.

"Rather than taking 100,000 people andgiving each of them an individual PCR, we can take the poop from 100,000 people and do one PCR. We get the same information," said Meddings.

He adds that monitoring the virus in wastewater is done at a much lower cost compared withPCR testing.

What the latest data shows about COVID-19 in Calgary

In Calgary, wastewater samples are collected from each of the city's three wastewater treatment plants one that services the bulk of the city in the north, and two smaller plants that service the south and far south.

Parkins says values in the data associate strongest with cases occurring six days after the sample was collected, benchmarked against Alberta Health Services' clinically confirmed cases. That means samples collected on Jan. 4 would predict the number of cases occurring on Jan. 10.

Results in the latest update on Friday which show samples collected on Tuesday predict that 2,305 to 3,534 new cases of COVID-19 would be reported on Jan. 10 in Calgary, if PCR testing capacity was the same as in the past.

"Our data trends up, up, up and while there are going to be individual dips and valleys in there, the overall trend is continued increasing case counts," said Parkins.

He says it's important not to overinterpret individual data points, such as apparent drops in infection, but rather understand trends over time.

And what does he conclude based onthe trends he's seen?

"I don't think we've seen the peak yet," he said.

The research team has seen increases in SARS-CoV-2 RNA values that were seven or eight times higher than they saw in preceding waves, says Parkins.

In those preceding waves, the correlation between wastewater infection and COVID-19 cases diagnosed through PCR tests was extremely tight, says Parkins.

But Meddings says that almost certainly won't be the case with Omicron, as the wastewater surveillance is measuring more asymptomatic cases.

Wastewater monitoring is most accurate measurement

Craig Jenne, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Calgary, says wastewater monitoring is the most accurate way to gauge how much COVID-19 is in Calgary especially with a lack of PCR testing.

He says it also gets rid of sampling bias that occurs with PCR testing.

"There will be a lot of people out there, for example, who may be asymptomatic, don't even know they have the virus. There may be others that are simply reluctant to be tested," said Jenne.

Unlike PCR testing, wastewater surveillance can also pick up on people who may have a novel or concerning variant.

However, Jenne says it has its limitations: wastewater data doesn't show where the virus is, who has it and how it's spreading. It also doesn't help experts understand the efficacy of vaccines or the impact of who has severe disease.

While wastewater monitoring is another tool to be used during the pandemic, Jenne and Parkins both say it cannot replace clinical testing or other protective health measures in the province.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)