'This was my last resort,' Ottawa-area woman says of experimental phage therapy to treat infection

Researchers believe viruses that kill bacteria may be an answer to antibiotic resistance

Thea Turcotte believes her life was likely saved by anexperimental treatment developed in Winnipeg for a chronic artificial joint infection.

"Without this trial, I probably would not be here by now," said the Ottawa-area resident,who isbelieved by her doctor to bethe first person in Canada to be treated with phage therapy for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI).

"It's given me a new lease on life. I'm just so happy to be here, to be able to be with my family, with my children, my grandchildren and great-grandchildren. I have a lot to live for," said Turcotte, 79.

Phages are viruses that target bacteria, invading them and replicating, then bursting out to search for more bacteria to kill. They do not infect human or animal cells. Researchers believe they also make antibiotics more effective by reducing the biofilm that surrounds and protects bacteria.

Phages were discovered more than a century ago byFlix d'Hrelle,a French scientist who later moved toCanada, but penicillin and antibiotics sent phage therapy to the fringes.

In Canada, it'sstill experimental and not available for health care outside clinical trials.Last year,researchers atSt. Joseph's Health Centre in Toronto completed the first Canadian trial on a drug-resistant urinary tract infection.

Eight years ago, Turcotte was an active retiree living near Ottawa, riding four-wheelers, walking and doing yoga.

But thenshe slipped on ice and shattered her hip and pelvis.

Since then, she's had 15 surgeries, "complete hip replacements on both sides ... with a lot of plates and screws. I'm full of metal."

'End of the line'

Over the years, Turcotte developed widespreadinfection. Last fall, shewas suffering from early signs of sepsis. Doctors were recommending amputation of her leg, she said.

Her case was complicated because the infection had become resistant to most antibiotics, she developed a "severe toxicity" to the only antibiotic that still workedand has a severe allergy to two of the major drug classes, said her infectious disease physician, Dr. Marisa Azad, whodoes research at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

"There was a pocket of massive infection that had opened up over the hip. She relapsed. She had early signs of sepsis. She had low grade fever, chills with increasing hip pain. So this is a very serious situation. I was extremely concerned," Azad said.

"I was extremely limited in what we could do to treat her. And really, this was the end of the line.... That's where I turned to phage therapy."

Health Canada approval for trial

Azad and her research team received rare approval from Health Canada to treat Turcotte in a single-patient trial, which issubject to the same regulations as larger clinical trialsunderCanada's Food and Drug Regulations.

In a statement, Health Canada said it "encourages and supports innovative research. Trials with a greater number of participants may support further development of drugs, and would allow researchers to gather more data."

Health Canada has been"extremely supportive. They know patients' lives are on the line," Azad said.

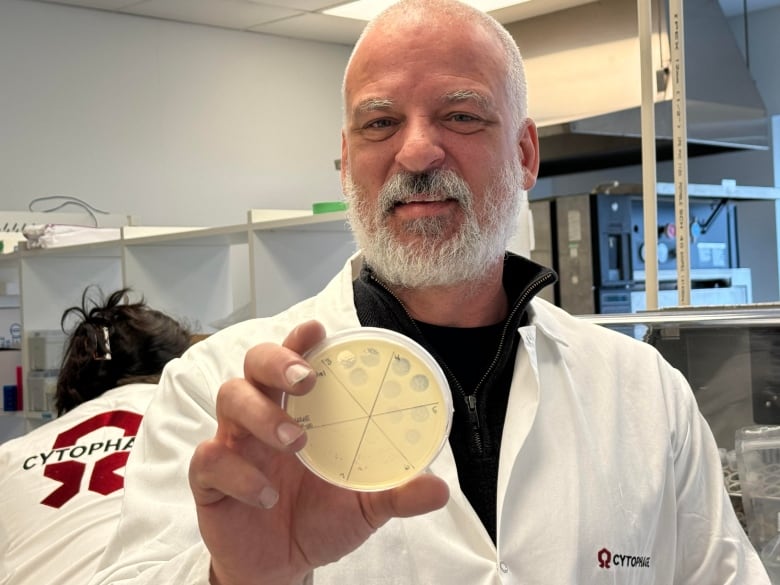

Azad sent samples of the Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteria from Turcotte's infection to Steven Theriault, CEO and chief science officerat Cytophage Technologies Ltd. in Winnipeg.

He and his team used that to create a phage specifically for Turcotte.

"What we do is ensure that our bacteriophage is killing the patient's bacteria at a very high level, so 100 per centor 98 per cent, making sure that we get rid of that bacterial infection creating a solution for patients that don't have any solutions because of antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic resistance," he said.

In February, Turcotte received the first dose of the phage. It was injected in her hip and then given regularly by IV over two weeks.

"There are early signs that she is responding very well to therapy, which is exciting and very promising," Azad said.

While she's still experiencing some pain, Turcotte is now recuperating with family in Eganville, Ont. She's able to get around with a walker and said she feels much better.

"This was my last resort. I had no other choice. So it was very scary. Also exciting. But I had to do it. It was do or die," she said.

"By me doing this, [I hope] that eventually it will be given to other patients who need it as badly as what I did, and hopefully making them feel much better and living a longer life."

Theriault said that's gratifying to hear, and the reason he got into science.

'A step forward'

"It's a step forward for bacteriophages. It's also a step forward for treating patients with debilitating diseases that can't be treated normally. And honestly, once we get the government to understand how phages are so beneficial, we're going to have a new therapy for patients which is going to be amazing," he said.

Witha growing resistance to traditional antibiotics, some European countries are allowing their use on patients.The British government is being urged to fund more research into phage therapy.

While it's still controversial, as scientists have a better understanding of how phages work, some say there is a moral and ethical responsibilityto research phage therapy as an alternative treatment.

Azad and Theriault will watch Turcotte closely and submit the researchto Health Canadawith the hope of doingPhase 2 and3trialsin a larger population. The regulator saysif those studies provide evidence of therapeutic valueoutweighingthe risks, they canfile for marketing authorization in Canada.

- How this couple used a bacteria-fighting virus to thwart a deadly superbug

-

'The enemy of my enemy is my friend:' Couple turns to viruses to beat back superbug

-

Viruses that kill superbugs could save lives when antibiotics don't work

"At the end of the day, what matters are patients," Azad said.

"A lot of the patients that I see with these infections, they have severe depression. They have suicidal thoughts. They feel like there's nothing they can look forward to in the future."

Some patients have amputations, along with chronic pain,and find itis "a terrible quality of life," Azad said.

"And for me to be able to say, 'You know what? There's hope. We're looking into this. This can potentially cure you. This can potentially lower your burden of infection. Let's try this.' And to see the hope that they have back that's worth more than anything."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)