Carbon pricing is here to stay in Sask. So how should the province use the money?

Paper looks at how four scenarios would affect people in different income groups

This Opinion piece was written byBrett Dolter,an assistant professor in economics at the University of Regina,Jennifer Winter, an associate professor in economics at the University of Calgary's school of public policy, and G. Kent Fellows, a research associate at University of Calgary's school of public policy.

For more information aboutCBC's Opinion section, please see theFAQ.

Following the Supreme Court's decision to uphold the federal carbon price, Premier Moe stated that Saskatchewan will create its own carbon pricing plan.

Premier Moe's first suggestion was that revenues would be used to reduce fuel taxes at the pump. Federal Minister of Environment Jonathan Wilkinson quickly poured cold water on that idea.

So how should Saskatchewan use the money it gets from carbon pricing, known colloquially as the carbon tax?

The good news is there are lots of options.

One would be to use the money to help balance the budget. Canada's Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) estimates that Saskatchewan will collect $659 million in carbon pricing revenues in 2021-22 (and this doesn't include revenues from the provincial output-based pricing system for large emitters, which requires companies like Evraz and K+S potash to pay for their pollution and places those proceeds in a green technology fund). If this revenue was simply added to our general revenue fund, we could trim 25 per cent off of the $2.6-billion deficit forecast for this year.

This would, however, spell the end of the climate action incentive rebates that each of us receives at tax time. When I file my taxes this year, my family of three will receive $500 for my partner, $250 for me, and another $125 for our child, providing a rebate of $875. If you look closely at your tax returns (specifically, Schedule 14), you'll find that you are also receiving a rebate based on the number of people in your household, with a 10 per cent supplement if you live in a small or rural community.

The province could also uphold the federal commitment of returning the majority of carbon pricing revenues back to Saskatchewan households. This would ensure carbon pricing doesn't reduce households' spending power.

Here is where things get interesting.

Looking at the possibilities

In an upcoming paper, Jennifer Winter, Kent Fellows and I evaluate four ways of recycling carbon pricing revenues back to households:

-

Focus rebates only on households below a certain income threshold ("Targeted Rebate to Low- and Middle-Income Residents").

-

Provide a rebate payment based on the number of people in a household, similar to the federal system ("Rebate to all Residents").

-

Lower the provincial sales tax ("PST Cut").

-

Increase the personal income tax basic exemption, the minimum income exempt from personal income taxes ("Increase to Income Tax Basic Exemption").

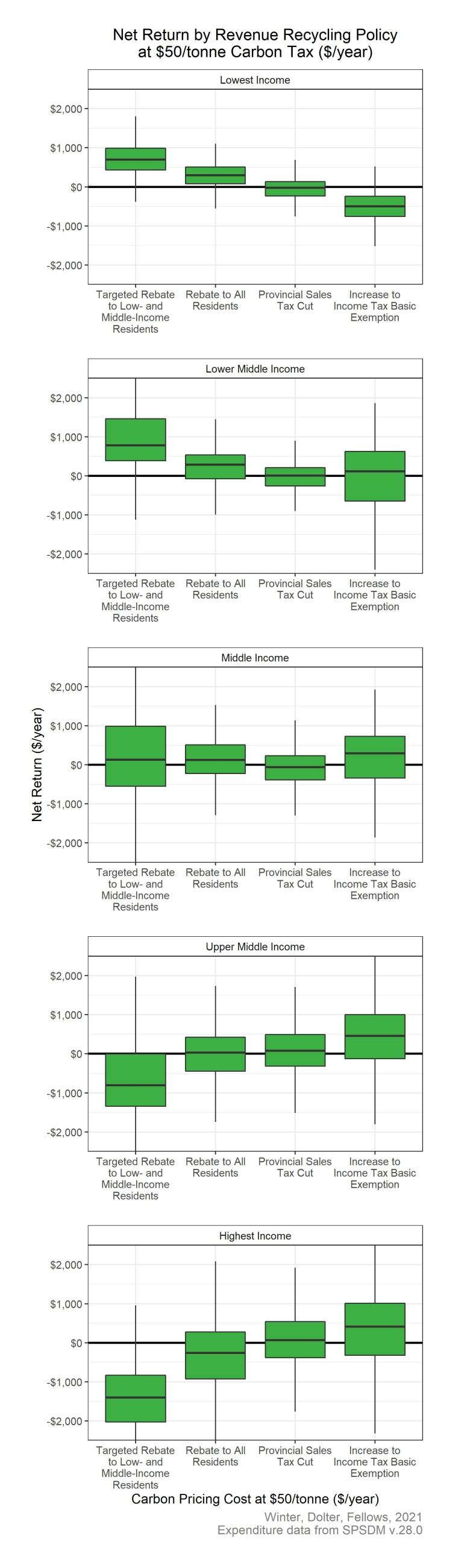

Our paper asks how households in Saskatchewan would fare under each option. Who wins and who loses? Would low-income households be better or worse off in each scenario?

We do this by dividing all Saskatchewan households into five equal categories, sorted by household income ("income groups"). Those in the lowest income group are the 20 per cent of households who earn the least. Those in the highest income group are the 20 per cent who earn the most. We then look at how each scenario would impact households in each income group.

We estimate how much households can expect to pay in carbon pricing, both directly (fuels like gasoline and natural gas) and indirectly (costs passed down from businesses). Our numbers assume businesses pass along all of their carbon costs to consumers, which is likely an overestimate.

We then use a simulation tool to calculate how much each household would get back from each scenario. We take that number (how much they get back) and subtract the first number (how much they pay) to calculate the net returns.

A clear picture emerges. A rebate targeted to low- and middle-income individuals makes almost all in the lowest income group get back more than they pay, while almost all in the highest income group pay more than they get back.

A rebate to all residents, similar to the current federal system, makes the majority of households in the lower four income groups get back more than they pay.

A PST cut ends up making about half of the households save money, but generally favours the higher-income households who spend more.

Increasing the income tax basic exemption and cutting the income taxes we pay would make the lowest income households almost universally worse off. Only 10 per cent of the lowest income group would see a net positive return, while the highest earners in the province would get the most benefit.

This table shows how each scenario is projected to affect each group, in dollars per household. A positive number means they are getting back more than they pay. A negative number means the opposite. In each group we also indicate the percentage of households that will get back more than they pay.

The income groups are represented as follows: 1 - lower income, 2 - lower middle income, 3 -middle income, 4 - upper middle income, 5 - highest income.

The table shows there are differences between income groups. There are also differences within the income groups. The graphs below show how returns for members within each group fall within ranges, with 50 per cent of the group receiving a return somewhere within the green bar. The black line within the bar shows the net return received by the median, or middle, household within the income group.

The choices for how to spend the money gained from carbon pricing have consequences. If we want to ensure that low-income households come out ahead, we could offer rebates only to individuals who earn below a certain income level, or provide rebates to all residents in the same manner as the existing federal rebate.

While a sales tax cut or increase to the income tax basic exemption might be appealing, they should be accompanied by additional supports for low-income households.

Remember that a carbon price works by sending a signal to reduce pollution, not by reducing spending power.

If you have ever had a swear jar in your house, it works along the same lines. Every swear means a toonie in the jar.Soon people invent creative substitutes to avoid the swear tax. But at the end of the month, the money is still in the jar and you can use it to order in pizza. We should remember the carbon pricing revenues don't disappear.

It's time for Saskatchewan to decide how best to use our carbon pricing revenues to ensure fair outcomes for the people of this province.

This column is part of CBC'sOpinionsection. For more information about this section, please read thiseditor's blogand ourFAQ.

Interested in writing for us? We accept pitches for opinion and point-of-view pieces from Saskatchewan residents who want to share their thoughts on the news of the day, issues affecting their community or who have a compelling personal story to share. No need to be a professional writer!

Read more about what we're looking for here, then emailsask-opinion-grp@cbc.cawith your idea.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)