'We decided to figure out how to love again,' Sask. residential school survivor says of long marriage

Elder shares story to honour students who died too young

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

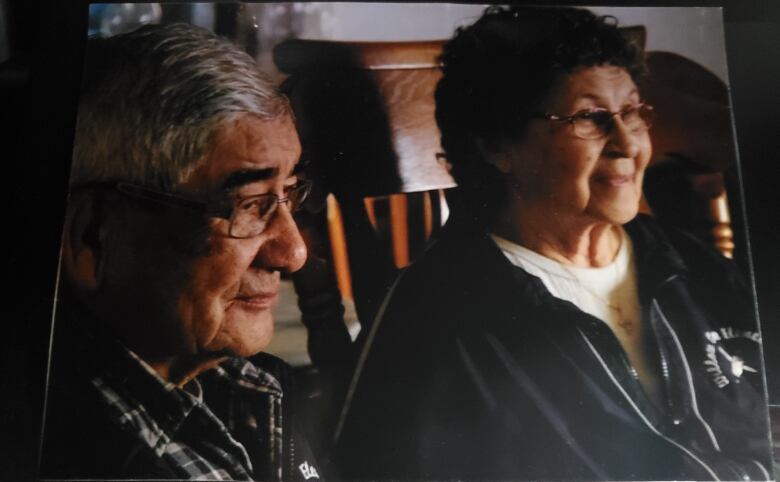

This is a story of one of Canada's longest-running Indian residential schools, but it's also a love story. This week, 91-year-old survivor Therese Seesequasis agreed to share that story to honour the thousands of children who died or went missing from schools across the country and never had a chance to find that love.

Therese Seesequasis remembers everything about her first dance with her future husband,Kenneth, in August1941.

"It was a waltz. I was only 12 years old. I was so nervous," she said.

Therese, Kenneth and the other St. Michael's Indian Residential School students were back home for the summer at the Beardy's and Okemasis' Cree Nation in central Saskatchewan.

When the music ended in the community hall and their families took them home, Therese and Kenneth didn't see much of each other for the next few years. He worked every summer. At school, the separation of the boys and girls was strictly enforced.

Abuse documented at school

The extreme deprivations and abuse perpetrated at St. Michael's have been documented and described by former NHL player Fred Sasakamoose and many others. In 1910, one Indian agent reported 50 per cent of all incoming students died of tuberculosis, a disease exacerbated by the unsanitary, cramped conditions atthe school.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission compiled a list of 3,200 children known to have died in Canadian residential schools. More than 100 of those attended St. Michael's, located in Duck Lake, about 90 kilometres north of Saskatoon.

The commission's report notes that these names form only a "partial record" and that the actual count is likely far higher.

In 1996, after more than a century, St. Michael's was one of Canada's last residential schools to close. The school building is gone, but dozens of stuffed animals and children's shoes have been left on the grass field following discovery of the remains of an estimated 215 childrenon the grounds of theKamloopsIndian Residential School in British Columbia. The Cowessess First Nation announced a preliminary finding Thursday of 751 unmarked graves at a cemetery near the former Marieval Indian Residential School.

Therese said this painful history must be exposed and remembered, but people also need to hear about resilience and love.

"I don't like talking about that anymore now. It's too emotional. I promised myself I wouldn't talk about St. Michael's this time. I did my healing," she said in an interview with CBC News, wiping tears from her cheek.

A happy courtship

Four years after that first waltz, on Aug. 7, 1945, Therese and Kenneth met at the exhibition in Prince Albert, Sask.

Therese wanted to try the roller-coasterbut was too afraid to go alone. She noticed a group of kids from Beardy's nearby and asked if someone would sit with her. Kenneth agreed.

The ride was much faster than Therese expected. Her long, frilly skirt flew up over her face.

"I was holding the bar with one hand and trying to push my skirt down [with the other hand]. It wouldn't go down. I was thinking, 'Oh my goodness,'" she said.

They got off the ride. Neither of them mentioned the skirt and they went back to their own group of friends.

A week later, Therese and Kenneth met at a wedding. They danced again and agreed to become boyfriend and girlfriend.

"I told him I always had a crush on him. He said, 'Me too. You're a doll.'"

Therese still had one more year of school, while Kenneth had graduated and was working at Beardy's. He said he'd wait for her.

For the next eight months, they caught occasional glimpses of each other when Kenneth and his family came to the school to visit siblings. They were not allowed to speak to each other.

Learning to love again

Therese finished school and returned to Beardy's. Eight years at St. Michael's had taken its toll on her and the other students. Even though the school was only 10 kilometres from Beardy's, her Cree culture seemed distant, almost foreign. She believed her parents didn't love her.

"I know that wasn't true, but that's what we thought. It was the same for Kenneth. Love was taken from us at the school."

Kenneth had waited for her. They spent the next year getting to know each other before getting married on Feb. 10, 1948.

"We decided to figure out how to love again. We promised each other we'd get that back," Therese said. "We were so poor, but we said our love would be enough."

They grew closer, began to trust each otherand started a family. A few years later, with the only good jobs in the community at the school, they went back. She worked as a cookand he was a maintenance worker.

Years later, their four sonsand four daughtersstarted their own families. Therese and Kenneth remained at Beardy's after retiring, helping to care for their grandkids.

At their 25th wedding anniversary dinner, in front of friends and family, Kenneth had to make a confession. He told the story of the roller-coaster and admitted he was sneaking looks while she tried to fix her skirt.

The couplebecame caregivers for the community, raising 29 kids from other families over the years.

Several years ago, Kenneth was diagnosed with cancer. In October 2017, just months shyof their 70th wedding anniversary, Therese visited him in the care home for the final time. He asked her to make another promise: If any child needs you, you will never say no. Therese agreed.

"It's hard to lose a partner. But we had a great marriage," she said.

"We tried to be honest, work things out, not argue so much. We always said we have to love each other because we lost so much love at the school."

Today, in addition to the couple's eight children and 29 kids from other families, they have 24 grandchildren, 69 great-grandchildren and 22 great-great-grandchildren.

Reliving a painful past

One of those grandchildren came to Therese'shouse. He drove her to the old St. Michael's site and told her about the discovery inKamloops.

"I couldn't speak. I felt like someone had a hand on my throat," she said.

A couple of days later, Therese and dozens of other residential school survivors attended an emotional ceremony on the school grounds. "How could this be? How could they do this?" she said.

As Therese and other survivors across Canada cope withtheir grief, she said it's important to share her story.

Inside the community centre at Beardy's and Okemasis' Cree Nation, a pouch of tobacco and baked goods have been placed on the table as a sign of respect and protocol for the interview. Therese's daughter, Emelda Seesequasis, sat with herthroughout.

Therese and Emelda said they're simply doing their best to chart a healthy path for their family.

Emelda said she knows her parents have always loved her, but she's never heard them say it. Emelda, who also attended St. Michael's, couldn't say those words for many years, either.

"My kids would say it to me and all I could say was, 'Me too.'"

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)