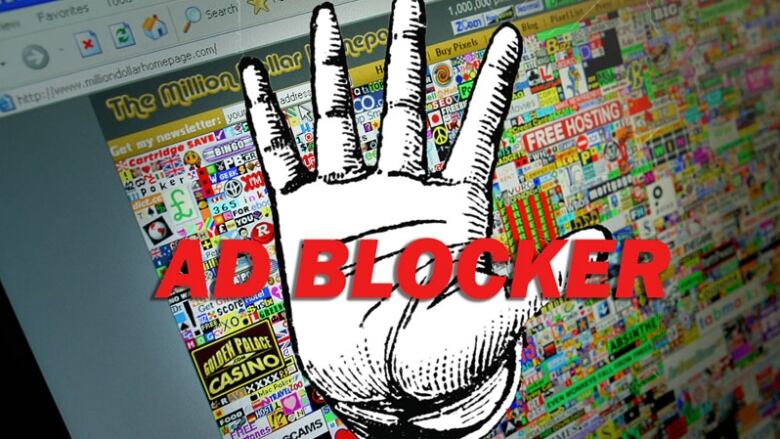

Why ad blocking hangs like a dark cloud over online advertising

Use of software to stop promotions appearing on screen on the rise

When the grandees of the global advertising industry met in the south of France earlier this week for the annual Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, they had much to feel good about.

Global ad spending is expected to reach $600 billion US by the end of next year, according to eMarketer, and grow at an annual rate of about five per cent until the end of the decade.Much of that growth is being fuelled by digital advertising, particularly on mobile devices.

- AdBlockPlus mobile browser could devastate publishers

- AdNauseam fights online ads by clicking on every one

But there was one session in Cannes where some very dark clouds managed to intrude on the sunny forecast. It was a panel devoted to the current scourge of the digital advertising industry ad blocking.

According to a report by PageFair and Adobe, more than 200 million people worldwide have downloaded software that can block virtually all online advertising.

The number of people blocking ads increased by more than 40 per cent last year, and it is estimated that blocking cost cash-starved publishers more than $22 billion last year.

- Also on The Sunday Edition, June 26, 2016

- Trump voters aren't who you think they are - Michael's essay

- HistorianMargaret MacMillanon "the morning after the night before" mood in post-Brexit Britain

- Poet Ben Lerner explains why he hates poetry -- and why you probably do too

So it's not surprising that just about any time advertisers and publishers get together these days, the question of what to do about ad blocking is usually high on the agenda.

The panel at Cannes was hosted by Randall Rothenberg, CEO of the Interactive Advertising Bureau, who has made no secret of his contempt for ad blockers.

At an IAB meeting in January, he described ad blocking as "an old-fashioned extortion racket, gussied up in the flowery but false language of contemporary consumerism."

White lists

The source of the ad industry's outrage is the ad blockers' practice of "white listing."Publishers and advertisers can pay an ad blocking company to have their ads appear on a user's page, even if the user has paid to have ads blocked.

- AUDIO: Ira Basen's documentary: If you use an ad blocker, you're killing the internet(Runs: 36:10)

The ad blockers defend the practice by arguing they only allow ads they deem to be "acceptable," but Kate Kaye, who writes about digital marketing for AdAge, isn't buying it.

"If I'm a consumer and I've downloaded that thing, I might be a little bit off-put by the fact that someone can pay to have the technology that I downloaded actually not work," Kaye said in a recent interview.

"I think it's analogous somewhat to mafia protection pay. It's like we're going to create a threat and then we're going to ask you to pay us to not threaten you."

Almost everyone in the ad industry acknowledges that most of the wounds that have led to the rise in ad blocking are self-inflicted.

Advertisers got greedy by assaulting users with too many low quality, untargeted ads, too many auto play videos, too much click bait.

Last fall, the IAB launched an initiative called L.E.A.N. Ads (light, encrypted, ad choice supported, non-invasive).

The IAB hopes that by following the L.E.A.N. guidelines, advertisers will create ads that consumers will be happy to see.

Playing hardball

But improving the user experience is not the only weapon in the arsenal. Some high-end publishers are playing hardball with readers who have installed ad blockers.

Sites like Forbes and GQ won't allow access to their content unless users turn them off. At Cannes, Mark Thompson, the president and CEO of the New York Times, announced that his newspaper would soon be offering an ad-free edition to subscribers at a premium price.

Other publishers are appealing to their readers' sense of fairness and justice, asking them to turn off their blockers and reminding them they are a critical part of the ecosystem that has powered the internet for the past 20 years. Without ads, there would be no free content online.

But Jess Greenwood of the New York ad agency R/GA doubts the effectiveness of appealing to users' better nature.

"Given the option to do the right thing or the free thing," Greenwood told the panel at Cannes, "consumers will always choose the free thing."

Native advertising

But the most effective strategy to counter the ad blocking surge might be to produce ads that don't look like ads at all.

So-called "native advertising" has been growing in popularity over the past several years. Also known as "sponsored content," it looks and feels like editorial content, but it comes from advertisers rather than journalists.

Native advertisements can often pass through ad blocking filters because the filters don'trecognize it as advertising. Many readers seem to prefer this kind of content over traditional advertising, provided it's properly labelled, although there's no consensus on what constitutes proper labelling.

- Online ad fight reaches new level with network-wide block

- Ad blocking will cost online publishers $22B this year, report finds

But the real victims of the ad blocking surge may not be advertisers and publishers, but the "free" web itself.

The money to pay for content has to come from somewhere, and if you take advertising revenue out of the equation, readers will have to pick up the slack themselves, something they have historically been reluctant to do. Without ads, the web may be a poorer and less interesting place.

It's hard to blame anyone for wanting to opt out of the increasingly unpleasant experience of surfing an over-commercialized web, and the consequences of those actions have perhaps not been fully realized.

"Things like the web can go," says Johnny Ryan, author of the book, The History of the Internet and the Digital Future.

"It came from somewhere. It's a fragile thing. It's supported by advertising and if we don't fix it, it won't be around for that much longer."

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)