ANALYSIS | Jeremy Kinsman: Can Europe be saved?

It has been a tough fortnight for Europe's struggling economies. In a double whammy, big institutional investors jacked up the price on government bonds, even for mighty Germany, while European banks faced a credit crunch that was stalling their ability to ease the debt fight.

On Monday, Nov. 28, European Union leaders are in Washington to brief Barack Obama and his cabinet on the so-called euro crisis. But as former Canadian ambassador Jeremy Kinsman observes, there may be a bigger underlying concern.

Is Europe really sinking before our eyes? What started as a government debt crisis in Greece only months ago seems to have deepened and spread almost beyond belief.

When I was there earlier this month I met so many Europeans in a state of shock. They don't get what has happened and they are not alone.

The crisis has several layers. On the surface is the debt of a handful of smaller economies in the 17-country eurozone. These are countries that over-borrowed and overspent, and which can no longer service their debt as interest rates spike.

Without a full restructuring of this debt by the solvent members, like what is being attempted now in Greece, there is the possibility that a handfulPortugal, Ireland, in addition to Greecewill have to default and perhaps leave the euro for their own currencies.

This uncovers a crisis deeper down of European solidarity.

The bond rates to cover these nations' debts are spiking because financial markets are skeptical that the solvent core euro-partners, especially Germany, will mobilize adequate relief for the indebted few.

That skepticism has now left even some of the bigger European economies such as Italy and France with financing challenges.

The debt crisis has thus become more deeply a currency crisis, which threatens the euro's future and, in turn, the entire single-market notion that is at the core of the post-War European Union dream.

Thus, the crisis becomes existential. Is the EU itself coming undone?

A fatal flaw

The EU's idealistic creators, starting in the 1950s right through successive deepening in the 1980s and '90s always intended it as a political project, envisaging "ever-closer union" which would end Europes murderous wars forever.

But they moved carefully, function-by-function, wary of confronting age-old national identities (like Britain's continuing euro-skepticism) head on.

The post-War economic miracle meant that Europe's citizens were healthier, and more peaceful, prosperous and green than ever before, in fact more so than anyone else on the planet.

But succeeding generations took these epoch-making achievements for granted.

Having shied away from federalism, the EU styled itself as a co-operative of national leaders in which all the important powers of taxation remained in national parliaments.

That way, national politicians could promise a wide variety of fiscal and social policies to get themselves elected.

That was to prove a fatal flaw for the eventual experiment of a common currency.

Too big to fail?

As the EU expanded from six to, eventually, 27"too far, too fast," claimed someit anchored democracy across the continent. But it also diluted a common loyalty.

Before long, populist, anti-immigrant parties, which were also anti-EU, began to rise everywhere, rattling governments who increasingly came to run themselves "against Brussels."

The result was that the EU was becoming too fractious and too big to govern. The assumption, however, was that it was also too big to fail.

However, as birth rates dropped way below replacement rates and the life spans of early retirees grew longer, the gilded pension programs and civil service jobs, particularly in the so-called Club Med countries in the south, became totally unaffordable.

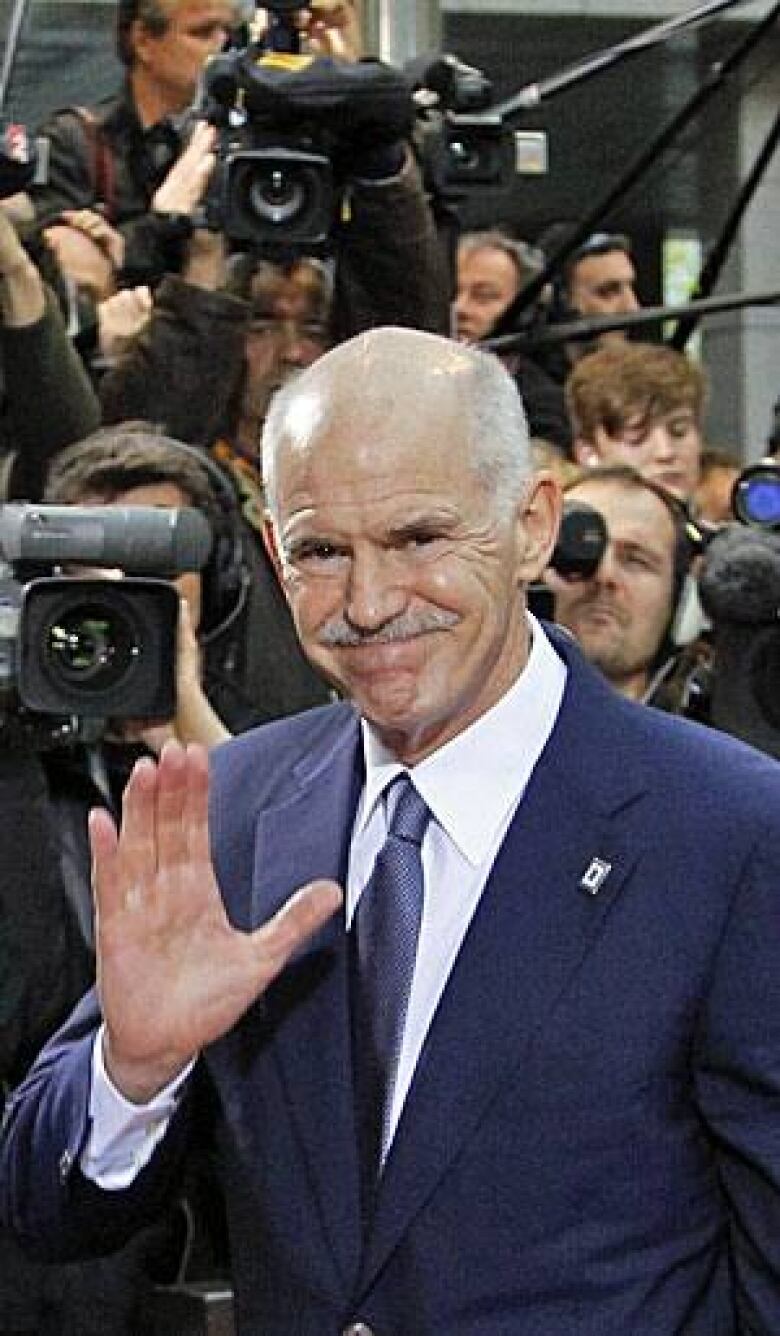

Rational analysis should have seen that Greece was heading for default a year ago, once it became clear that the previous government had simply lied about the size of its deficit (12 per cent of GDP instead of the six per cent it claimed).

But Greece got away with it because the European Central Bank, in the co-operative mindset that permeated the EU, was not given the tools to hard-check member states' numbers.

Playing for time

A robust and swift re-financing package a year ago could probably have saved Greece then, albeit with some "haircuts" for European lenders.

But Greece's euro-partners, especially Germany, played for time, hoping the problem would ease.

They didn't want to have to explain to the upright, tax-paying northern electorates why it was imperative to support the ostensibly free-loading Greeks.

Nor did they make it clear that the ongoing benefits of monetary union were at risk, possibly because they couldn't see that far ahead or were terrified of the electoral consequences. (As Luxembourg's prime minister, Jean-Claude Juncker, put it, "We all know what we have to do. But how do we get elected afterward?")

But now, the debt crisis, the currency crisis, and the existential EU political crisis have come to a head and have to be seen as one. Cosmetic surgery won't work. So what is to be done?

What next

Whatever happens will require German leadership. Germany is the EU's biggest economy and the euro's financial muscle.

And while there is evidence that Chancellor Angela Merkel sees the full dimensions of the crisis, calling it Europe's "darkest hour" since the Second World War, she is clearly hamstrung by the German bias against the only possible solution: to strengthen collective financial action at the centre.

Still locked in its historic phobia over inflation, Germans have resisted, as recently as last week,empowering the European Central Bank to take over and become the lender of last resort, fearing it will just print more money.

But the German co-op approach was tried and failed to raise the huge amounts of money required to stabilize the continent.

And Germans now face the tough choice of whether to give up fiscal sovereignty and embrace a robust backstop role for the ECB; or put the euro and ultimately perhaps the EU itself at risk.

If Merkel is forced to come around, changing the central rules of the EU game will bring "more Europe" into peoples' lives just when the prevailing sentiment has been running in the opposite direction.

Britain's euro-sceptics will squawk at the emergence of an inner and an outer EU, as the remaining eurozone economies would inevitably act in closer consort. But the Britshave no positive alternative to offer.

We North Americans have a big stake in the outcome and should continue to push for more centralized decision-making over there.

Our financial exposure to European bonds has been greatly reduced. But any further European downturn would wreck the U.S. hopes for a recovery, with inevitable political impact, and Canada would feel the cold.

The creation of the EU is one of history's great remedial narratives. World peace, security, prosperity and democracy are much more obtainable with a healthier Europe than without it.

At this juncture, in particular, we all need Europe's better angels to come to the fore.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)