Syria's civil war: No good options and so many 'known unknowns'

What is so striking is how little is known on either side of the debate, Brian Stewart says

Good minds on both sides of the Syria debate find themselves struggling to stake out positions amid a clash of awful alternatives, worst-case scenarios and unknowable consequences.

A civil war of almost unwatchable brutality now provokes a debate of singular complexity. Even for those who firmly believe the regime did use banned chemical weapons, there seem to be no good options.

As British Prime Minister David Cameron found to his shock in Parliament, even some conservative hawks are wavering. In the U.S., two sides face their own doubts.

Those ready to justify President Barack Obama's plan to "punish" the Syrian regime for having crossed the so-called red line know the gains may be limited and risks enormous.

On the other hand, those strongly opposed to the military strike at least have to consider the possibility that failure to punish Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's apparent use of such weapons may encourage their further use, in Syria and elsewhere.

What is so striking about this debate is how little can be known on either side.

There is lots of evidence the regime laced a suburb of Damascus and other areas with lethal chemicals but not the smoking-gun, absolute proof that critics hoping to prolong inaction insist on.

No quick fix

For their part, supporters of a strike can promise no quick fix. Assads forces would be hurt, but not too badly. Theyd be stung, but not staggered to the point of crumbling before a rebel force Washington does not want to see victorious in this war.

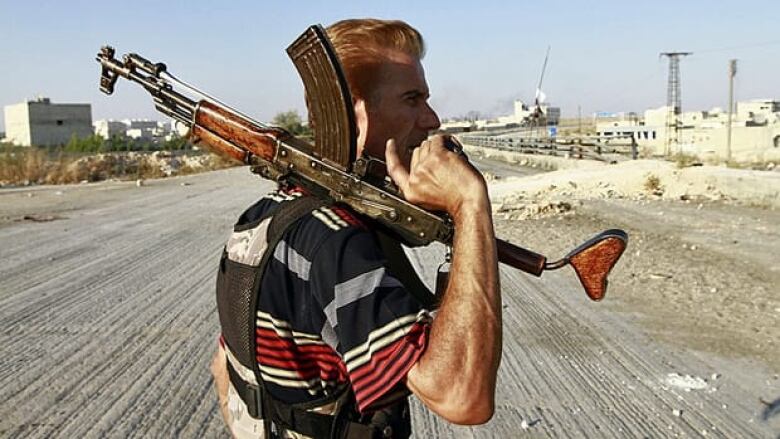

The loose rebel alliance is made up increasingly of Islamist hard-liners, some with links to al-Qaeda.For the U.S. and much of Europe, their victory is one of those worst-case-scenarios in play.

So this means the U.S. strikes will use long-range cruise missiles and other sophisticated weapons all delicately calibrated to ensure Assad forces are damaged but not destroyed.This means the war that has already killed more than 100,000 people and made seven million refugees will continue.

In short, the strikes will exert no outside leverage to halt a war that has for 2 years destabilized the whole region and given al-Qaeda lush new sanctuaries in northern Syria.

What's more, at this point no one can claim to know how Assad an enigma to foreign intelligencewill react. (This is surely one of those "known unknowns," to use a famous expression of former U.S. defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld). Some analysts believe Assad will simply shrug off attacks while revelling in the role of one who defies "American bullying."

Others believe he's desperate enough to wreak havoc even against hostile neighbours such as Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon, perhaps even Israel.

Hopes that he might be chastened enough to seek a diplomatic solution to the war seem based on little more than wishful thinking, at least as long as Vladimir Putin's Russia remains in Syria's corner, ready to supply arms and effectively block any United Nations intervention.

Limited deterrent

Defenders of a strike have made a strong argument, convincing to many, that it will at least punish the atrocious use of internationally outlawed chemical weapons and persuade other nations that such use is too dangerous to contemplate. The strike, they argue, is a deterrent, but a limited and short one.

They raise the question: What value will any international restriction on weapons of mass destruction have if their use goes unpunished by the world? And while all might prefer the UN to do the deterring, when it cannot, must not others step in to act?

Every aspect of this debate is haunted by the Iraq war, however, and memories of 2003 and the Bush administration's abuse of similar arguments about weapons of mass destruction that allegedly threatened the world but turned out to be desert mirages.

This is a different time, a different crisis and a profoundly different White House, but still, once shattered, credibility on foreign policy is notoriously hard to repair.

The drumbeat of U.S. intelligence scandals in recent years has only added to world-wide doubts.

In the face of public and political hesitation, those supporting the strike argue that both Obama and America's credibility are at stake and to back down now willonly encourage others to test U.S. resolve across the world.

"The world will not see this as prudence, but rather as dithering," writes Vali Nasr, an international scholar and writer at Johns Hopkins University.

"That will embolden America's adversaries and deject its friends. American could soon find itself alone in standing up to Iran or North Korea, or pushing back against China or Russia."

Lacking credibility

Critics of the strike argue Obama boxed himself into this position by all-too-vague talk of "red lines" without a clear strategy.

They'll further argue that any attack launched with little hope of any gain except to restore a president's shaky credibility won't be all that credible in any case.

If national credibility haunts one side of the debate, however, the other is confronted by a disturbing reality that inaction may, at least arguably, have frightful consequences in years ahead.

In the clear absence of effective diplomatic deterrent, and if the world cannot enforce some enforceable red line against the use of long-banned chemical and biological weapons, a whole range of nightmare scenarios becomes possible.

For what brutal regime in the future need ever fear for its continued existence in the face of mass democracy protests or civilian insurgency when such weapons are at hand?

Whether chemical or biological, these weapons are cheap to make, easy to conceal and, as weve again seen, utterly gruesome in effectiveness.

Who would protest en masse?

The original international bans on the weapons were to suppress their use by armies against armies.

Now that we've seen adults and children writhing in death agonies in Syria, we may consider the more serious threat is their use to suppress populations.

For who anywhere would even dare to gather in large numbers to protest or to rebel in the face of even the threat of such an attack?

The Syria crisis now raises so many issues, doubts and moral uncertainties that the debate over the coming weeks will be fascinating but also deeply troubling.

It comes down to the fact one can be deeply torn at the same time both by the threatened U.S. strike and by the thought of the world again doing nothing to stop the use of such weapons.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)